“Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts.”

― Richard P. Feynman, The Pleasure of Finding Things Out

A long time ago, humans invented a very useful process for sharing information. It works like this:

We become interested in a topic.

We ask questions about the topic.

We come up with a few guesses for what the answer might be.

We test our guesses.

We write down the guess that matched reality.

This simple process is the fundamental building block for progress. At its core, this is what science is all about.

Recently, I've noticed a dangerous trend: it's become more difficult to ask basic questions. Certain topics have become so politicized that they split a conversation right down the middle. You either agree with the group, or you keep your mouth shut for fear of being ostracized. We've all started acting like politicians: we watch our words and tip-toe around subjects that might set off a chain reaction.

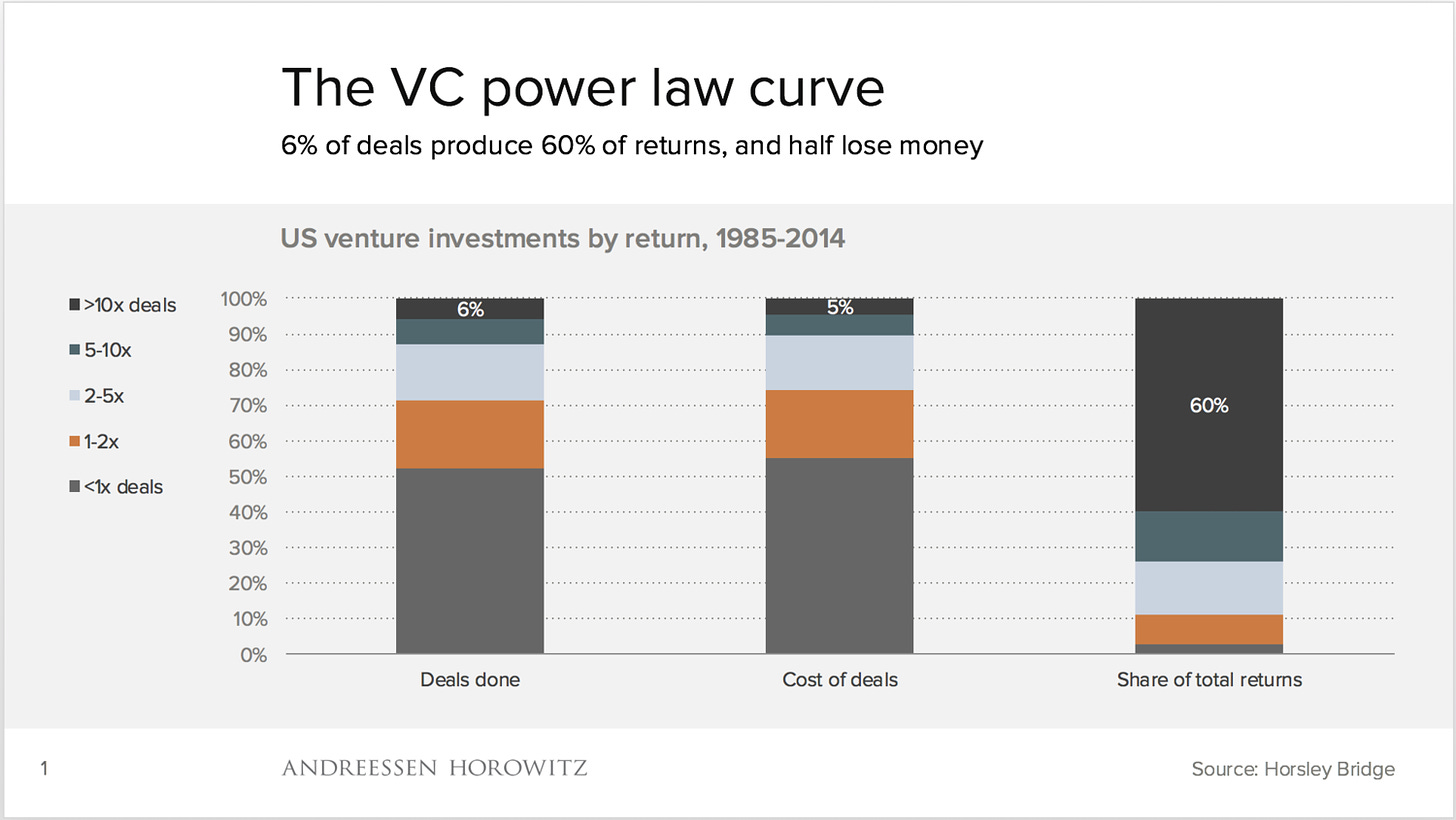

This trend is dangerous because it snips the process of discovery at its root. If we can't ask questions, we won't find new answers. And, as we've seen from the venture capital industry, it's very difficult to predict which questions (or companies) are worth investing in. We're only able to determine ex-post that a question was worth asking.

“Reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.”

― Richard P. Feynman

For specialized knowledge like healthcare or law, there are many questions to ask. It's unrealistic for the average person to learn answers for every field, so we rely on experts to keep us informed. In many cases, these experts are no smarter than you or me. They just happen to have spent more time learning the common answers about a topic.

When experts start preventing people from asking questions it means there has been a breakdown in the process. Experts do not have a monopoly on asking questions. Many breakthroughs have come about as a result of those who are willing to ignore expert assumptions. To see what is obvious often takes an outsider.

There is a common misconception that the average citizen lacks the critical thinking capabilities required to find answers to questions. We assume that because experts have years of schooling, they must be the best prepared to ask questions. I'm here to tell you that a college education has nothing to do with it.

In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig writes:

An untrained observer will see only physical labor and often get the idea that physical labor is mainly what the mechanic does. Actually the physicial labor is the smallest and easiest part of what the mechanic does. By far the greatest part of his work is careful observation and precise thinking.

In this paragraph, Robert is writing about the scientific process as applied to the art of repairing a motorcycle. We don't typically think of vehicle maintenance as "science", but the process is similar. A problem is identified, and steps are taken to answer the question. Unlike the fuzziness of other fields, it's easy to tell when a mechanic has done their job. Does the car run? Is the problem fixed?

This is the scientific process in action.

The tendency to ignore questions from non-experts has caused us to throw away our common sense. We see the broken motorcycle in front of us, but we're told by experts that there is no problem to be solved. It's "above our pay grade", so we assume the misunderstanding must be some fault of our own. Like a student with a condescending teacher, we've been shamed into keeping quiet.

Until we start thinking of ourselves as intellectual equals we won't see improvement in our institutions. This means taking responsibility for our opinions instead of blindly accepting what is handed down to us. It means thinking critically not only about what is true but why it is true.

Common sense means asking questions, even if you don't know the answer.