It is so shocking to find out how many people do not believe that they can learn, and how many more believe learning to be difficult.

Frank Herbert

One of the most underrated aspects of the internet is that access to education doesn’t end after school.

Until recently, this type of lifelong education just wasn’t possible. Universities had a monopoly on the research and literature of academics. If you wanted to learn about an advanced topic like science or technology, you needed to go back to school or work for an academic or industry research institution.

Today, you can access a world-class education for the price of a laptop and monthly internet connection. It seems like this would be a slam-dunk, but most people don’t take advantage of this fact.

I believe that the problem isn’t a lack of content, but a lack of structure. Universities are successful because they provide structure and community for their students and faculty. Without this structure, most people find it too difficult to continue learning in an organized manner.

This essay will explore the question: what if education didn’t end?

Over the next few weeks, this newsletter will discuss various aspects of education. First, we will examine global education trends and what these mean for society. Next, we’ll evaluate the different options available today for post-primary education. Finally, we’ll take a look into the future and imagine what an internet-based education would look like throughout a lifetime.

If you know someone interested in education, including global trends and strategies for academic success, consider sharing this post with them.

Education globally

It’s essential to understand how education looks around the world. One of the most encouraging global trends is the number of educated adults. Today, over 80% of all people over the age of 15 have received some formal primary education.

Basic education, also known as primary school, is crucial because it teaches fundamental literacy and numeracy skills that allow adults to participate in the global economy. Learning isn’t just for the elite — an educated population correlates with economic growth.

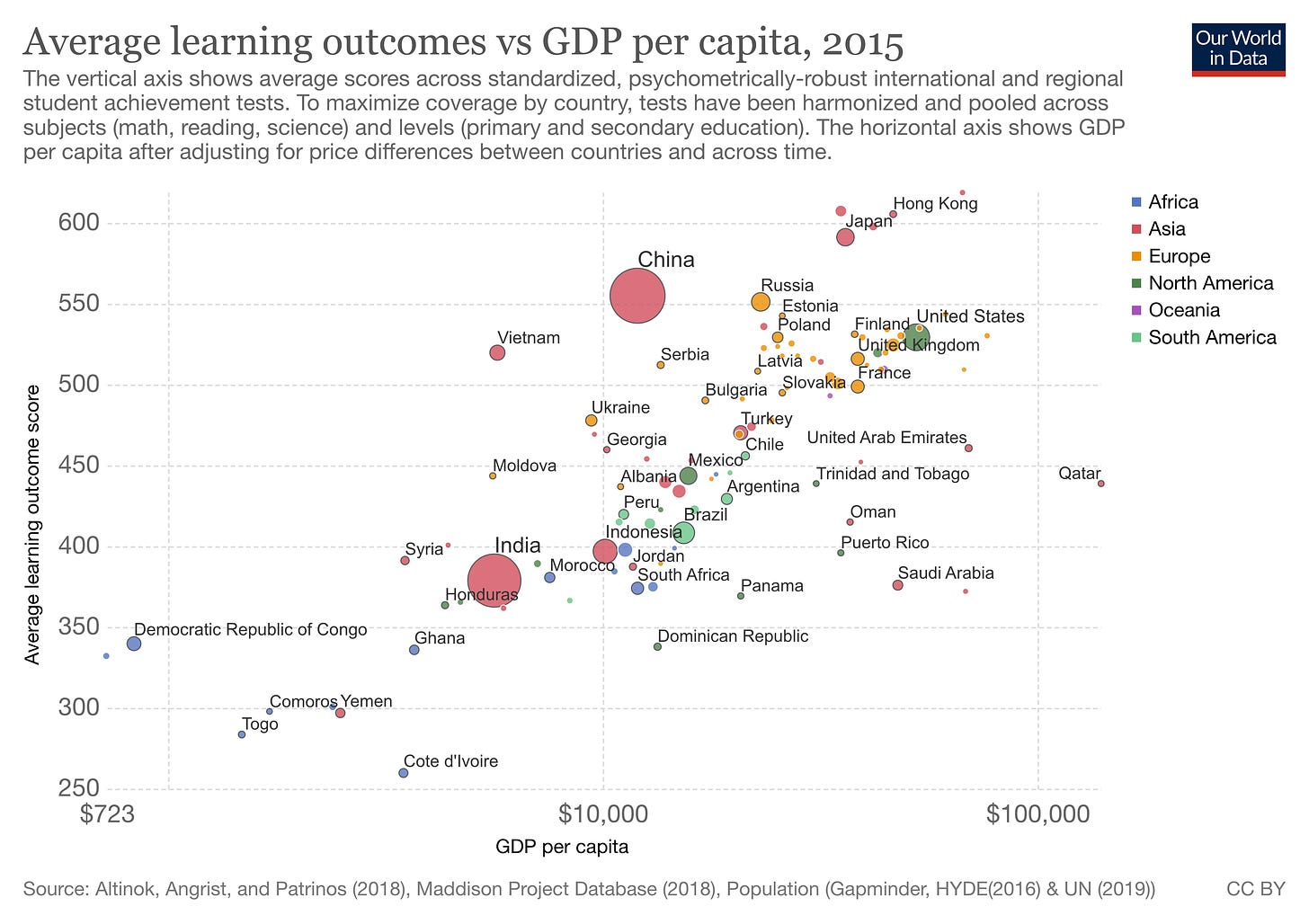

The graph above shows the association between test scores and long-run economic growth after controlling for baseline GDP and years of schooling.

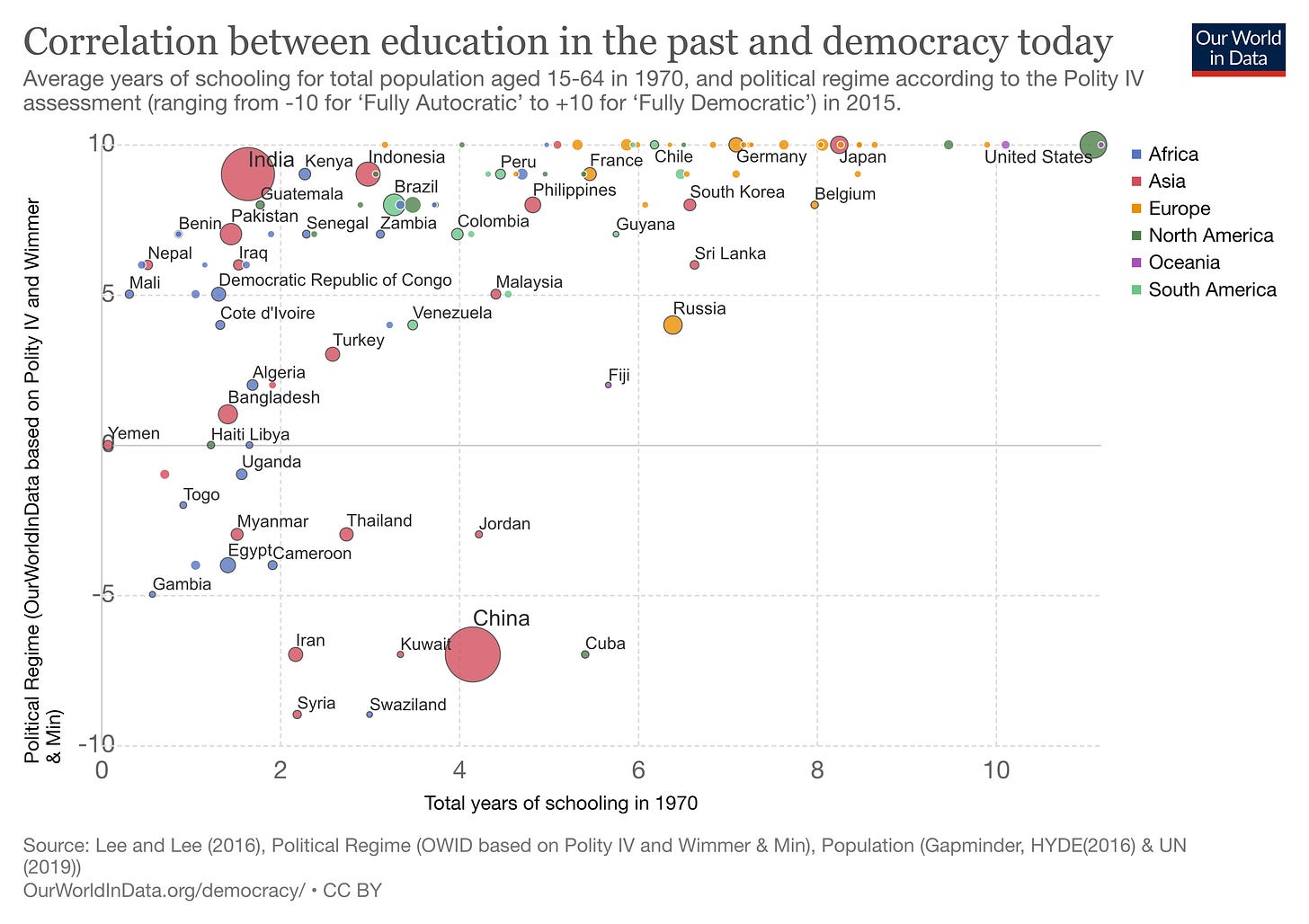

There are also theories that a well-educated population is a precursor for democracy. Historically, countries with populations that received more than four years of school on average are more likely to be democracies in a few decades. This foundation is important because it gives our government other options for influencing the outcome of countries without resorting to political or military initiatives.

As I’ve stated before, I believe that the increasing number of people living in democracies is a positive trend. An unusually long-term thinking administration may choose to realize this goal with education, rather than force. Instead of sending in an army, they will send in tutors and academics, and wait for those children to grow up.

Other important trends tied to education include:

Our society is focused on increasing primary education around the world — as we should be. Progress over the last century has been phenomenal, but there is still much work to do. This is especially true in places like Sub-Saharan Africa, where 20% of children who are primary aged are out of school. This has a significant impact on our future and the future of children who are not receiving educations today. By examining SAT scores of first-generation college students, we know that parental educational levels influence academic success for their children.

If we assume that education has a causal effect on GDP growth, then a generation of uneducated children will create repercussions that last for decades. Compound growth is a powerful force, and the impact of investing in primary education today will have outsized returns through the creation of more doctors, scientists, and engineers.

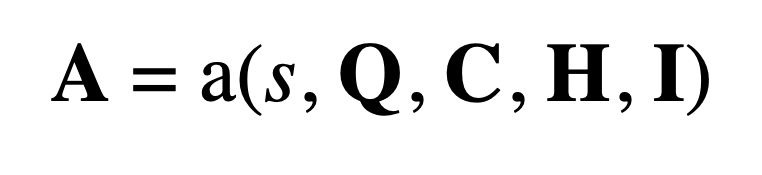

Of course, not all education is the same. Specifically, several factors predominantly affect the quality of education. The following formula can helpfully represent these, called the “Education Production Function” from the Handbook of the Economics of Education:

In the above formula:

A represents skills learned

s is years of schooling

Q is a vector of school and teacher characteristics (quality)

C represents individual characteristics (innate ability/aptitude)

H is a vector of household characteristics (home situation)

I is a vector of school effort decided by households (attendance, supplies)

To effectively increase A, it is possible to target any one of the above variables. The wide variance in global education outcomes shows that education is not merely a result of pouring in cash — the social determinants of school are just as essential to achieve a good education.

You can think of Q as a supply-side input, and C, H, and I as demand-side inputs. Each variable will respond differently to incentives, and I’ve highlighted some popular strategies below.

Years of schooling (s)

The years of schooling that an individual receives are the metric that we typically use in our daily interactions. Job applications will often ask for the highest level of education as a filtering mechanism for specific roles. Knowing that someone has a Ph.D. may qualify them as an expert in your eyes, even for problems that are unrelated to their field of study. Years of schooling is also the metric that is most easily influenced by the spread of the internet. It is now possible to continue to increase s throughout a lifetime, for little to no cost.

Quality of teaching (Q)

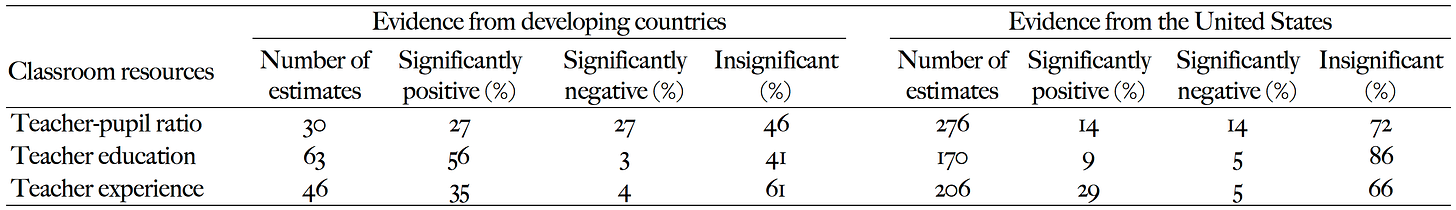

The characteristics of a school are also broadly important. This is not only the facilities but also the quality of the teachers, students, and programs. Interestingly, this variable is a vector: it has a magnitude and a direction. This means that not only can the quality differ from school to school, but it can also harm the result. For example, we know that improving teacher quality is often a better strategy than merely improving the student-teacher ratio.

The table below shows findings from the literature that examine the effect of teacher-pupil ratio, teacher education, and experience on student outcomes. Although the effect sizes are small, the relative impact of teacher education and experience as measured by “significantly positive” results is higher across both developing countries and the United States.

Household characteristics (H)

Not being able to attend school because of health problems or a bad home situation can invalidate nearly any investment in the quality of the teaching environment. Home situations are challenging to control for, since they happen outside of the learning environment. However, some strategies have shown promise.

The most common strategies for equalizing household characteristics are financial-based scholarships. Scholarships give students from less financially secure backgrounds the opportunity to participate in higher education.

Non-financial incentives, like guidance counseling and mentoring, are also useful. By providing students with information about career options and pathways, students whose parents do not come from educated backgrounds have access to the same opportunities as affluent students. As always, it’s difficult to mitigate the network effect of upbringing completely, so the best strategies for children in the future are making sure their parents receive an education today.

Individual characteristics (C)

Individual ability is highly variable, and perhaps the most difficult to control. For most students, their capacity will follow a normal distribution, and time is better spent on improving the other variables in the education production function.

However, in circumstances where an individual possesses innate ability but is simply behind their peers for some reason, remedial interventions have been shown to help. Receiving dedicated tutoring or focused study can bring individuals up to speed, as long as the teacher possesses the right combination of experience and education.

School effort (I)

School effort is another way to think about the ability of the student to apply themselves to their studies. This is highly dependent on both their home situation and level of preparedness. A brilliant student who never shows up to class because of a lack of transportation is unlikely to display academic achievement.

These problems can be mitigated by schools that create an environment that does not disadvantage students with atypical situations. For example, offering classes for mothers that would otherwise be absent can improve the input of students in this situation. Similarly, making sure that students have adequate supplies to complete their required activities is a quick way to boost their effort.

Intrinsic motivation is essential, so studying a topic that is interesting to you will naturally increase this factor. If it doesn’t seem like work, you’re more likely to put in the extra hours needed to succeed.

Bringing it together

To summarize, I’ve compiled the takeaways and common strategies into a helpful table.

The trend towards an increasingly educated global population is encouraging. Understanding that education has essential effects on childhood mortality, GDP growth, and social behavior helps to frame the size of the opportunity for policymakers. Primary school is especially important because it cements an intellectual foundation for the rest of a person’s life.

The first step in asking what would happen if education never stopped is understanding what it’s like for those who never started.

If you enjoyed this essay, please consider sharing it with a friend. Sunday Scaries doesn’t have paid subscriptions yet, so the best way to help support this publication is to spread the word.

Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that answers simple questions with surprising answers. It’s part soapbox, part informative. It’s free, you’re reading it right now, and you can subscribe by clicking the link below. 👇

Photo by Doug Linstedt on Unsplash