Momentum and Becoming a "Rolling Stone"

Momentum is one of the most underrated factors in getting things done. Although this concept is well understood in sports, we seem to ignore it for other aspects of life.

When a team is coming off of a win streak heading into a big game, we take it for granted that their chances of winning are higher. Being on a hot streak is more than a statistical quirk; it influences how players act and think. When you have momentum, your brain is making connections on the top idea in your mind in a way that improves performance.

One of the problems with work today is that we never let ourselves get into a hot streak. A big factor here is the way that most work is structured. Corporations are not designed for teams to gain momentum; they’re designed to prevent momentum from going to zero.

The typical work-week gets everyone to the same place at the same time, regardless of whether or not a 9-5 schedule is suited to the job. This compromise helps create a baseline level of productivity, but limits upside. Some of the most successful products and creative works in history have been created by teams working on intense schedules with a defined end date and clear objective.

Examples of projects with momentum

Patrick Collison maintains a list of these types of projects on his website. Their shared characteristic is that they were completed unusually quickly. I won’t duplicate the list here, but it’s worth highlighting a few examples:

The Empire State Building. Construction was started and finished in 410 days.

The Federalist Papers. Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay published 75 essays over 151 days. (A further 10 were published on a somewhat more languid timeline.) All but five were written by the former two authors. In that initial 151 day burst, Hamilton published 41 essays; on average, 1 every 3.7 days (while also working full-time as a lawyer). The essays have since been quoted in 291 Supreme Court decisions.

JavaScript. Brendan Eich implemented the first prototype for JavaScript in 10 days, in May 1995. It shipped in beta in September of that year.

Boeing 747. Boeing decided to start the 747 program in March 1966. The first 747 was completed on September 30 1968, about 930 days later.

These projects stand out not because of their similarities, but because of their differences. Timelines range from days to years, but the impressive part is the rate of progress in relation to similar projects. The conditions surrounding these projects allowed teams to gain momentum and work very intensely over a relatively short period compared to other efforts.

Why do we lose momentum?

Momentum is how much you’re doing times how fast you’re doing it. To gain momentum, you need to add energy faster than friction can remove it. Adding energy to a project means focusing, whether it’s for a day, a week, or a month.

I think there are a few main reasons why teams lose momentum:

Work is broken into arbitrary five day chunks

Teams are made up of people with different priorities

Today, we’ll address techniques for breaking up our work. In another essay, we’ll discuss how teams decide what to prioritize. Finally, we’ll bring that all together into a strategy for gaining momentum, even if your environment is not ideal.

Working in chunks

Workings in chunks is bad because it causes you to lose focus. Hard problems have a tendency to take up most of the available space in your mind. We’ve all had the experience of tossing and turning, unable to turn our brains off. Working on a hard problem for a stretch of time is like this, but you get answers along with your sleeplessness.

One of my most unpopular opinions is that weekends are basically arbitrary and do more harm than good. As you can imagine, I don’t share this one publicly because I know I’ll be ostracized. Let me attempt to summarize my position:

Weekends break work into chunks, regardless of whether or not teams are making progress on a problem. Throwing on the brakes in this scenario would seem ridiculous in any other setting. Imagine your favorite sports team decided to spend the week before the championship game not practicing, and showed up on game-day against a team who had spent the previous week in training camp. The team chemistry alone would be a significant advantage, not to mention the preparation time. This is basically what we are doing with weekends, except no one is buying your jersey.

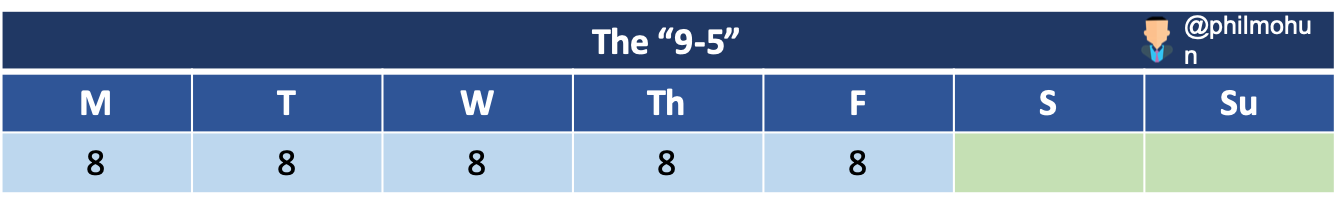

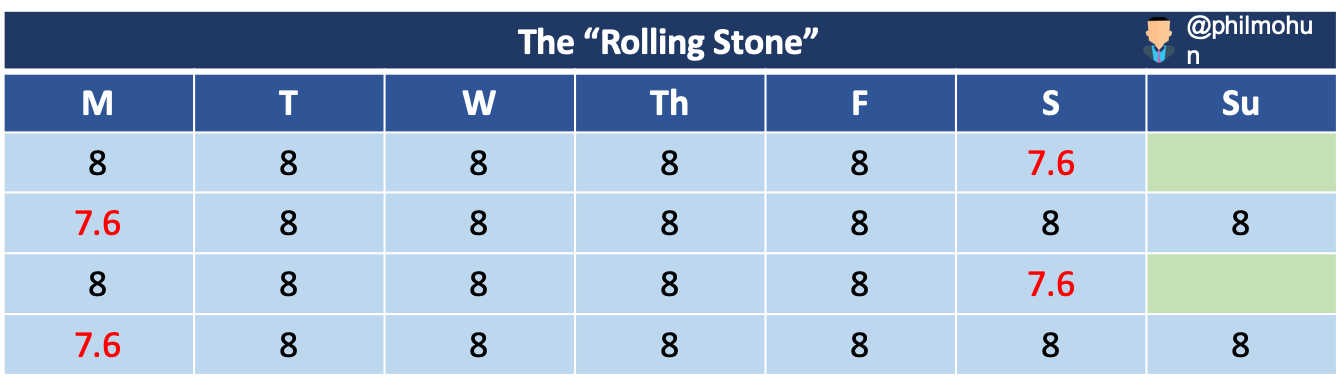

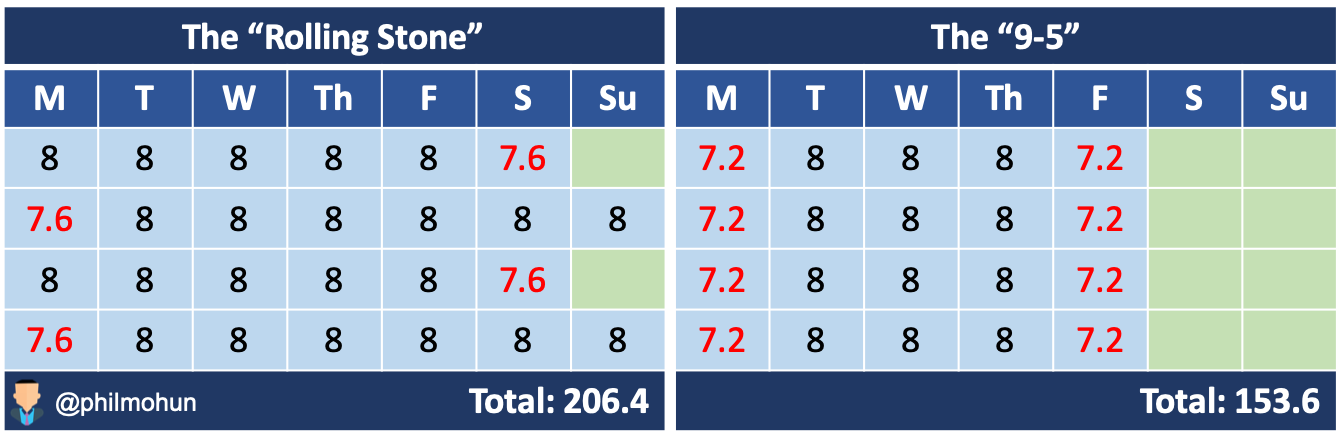

Consider the current status quo; the “9-5”:

The 9-5 means that you have ~8 hours per day to get work done. Fridays are typically less productive because people know that anything they start will need to be put down for two days. Dusting off the laptop on Monday morning means a reboot of all the momentum you had gained by Friday.

Assume that each day adjacent to a break accrues some productivity penalty. The longer the break, the larger the penalty. For our example we can be generous and assume it is only 10%. The hours of productive work now look like this:

90 minutes per week may not seem like much, but in an organization of 20 people, this is like removing an entire person from the staff over the course of the year.

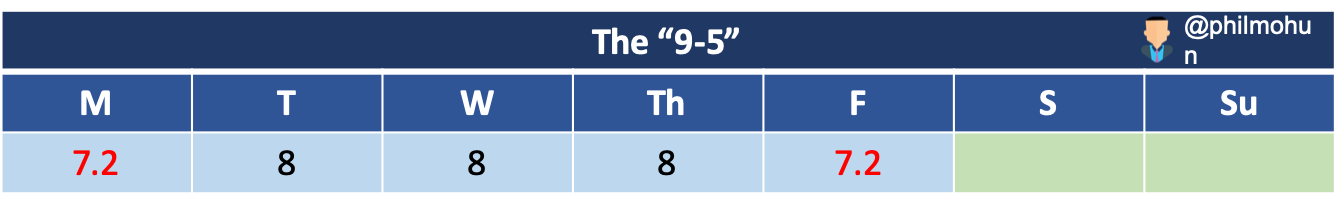

There are other suggestions that get floated around, one of which is working 10 hours a day, 4 days a week. Let’s take a look at that example:

I’m generally skeptical about working long hours in a single day, and in this example we’ve now actually lost 4 hours a week, due to a 20% knock of productivity from the longer break.

These examples are obviously illustrative and may depend on other factors. The point is to show that the typical idea of work-life balance is not actually what people want.

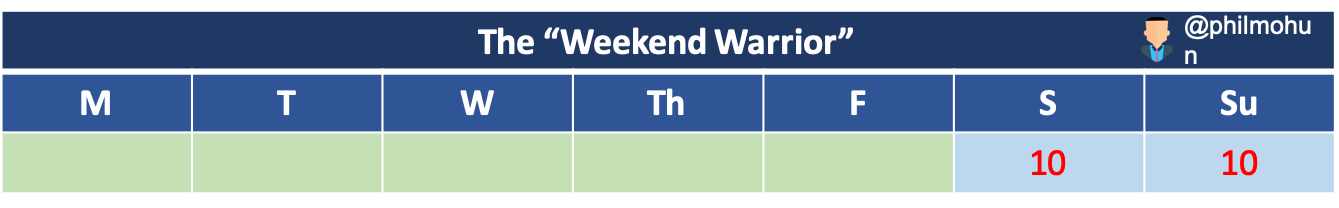

We all know someone who lives for the weekend. For this person, the thing that kills their momentum isn’t the two day break from work, but the five day break they take each week from what they really want to do. Inverting the chart shows how much valuable time they get from their weekends.

For the Weekend Warrior, they are losing time by spending their weekends doing the mundane things they don’t have time for during the week. Their 12 hour day is being cut into by errands, chores, and playing catch up on sleep.

I’m not saying that we should get rid of weekends, but merely that they lower the momentum of most projects. Instead, I believe the solution is to work in bursts: focusing on one project for a period of time, and only stopping once a significant milestone has been achieved. This maximizes the momentum gained from working, and longer breaks offset the missed weekends.

I call this strategy the “Rolling Stone”:

Like a rolling stone, this schedule lets you gain momentum on projects, while minimizing the friction from stopping completely. Compared to a typical 9-5 over the course of a month, this schedule results in an extra week of productivity.

Of course, not everyone is interested in working all the time and burnout is a very real thing. The Rolling Stone schedule works best when interspersed with extended periods of rest, meaning a much more rewarding break than the frenetic pace of weekends.

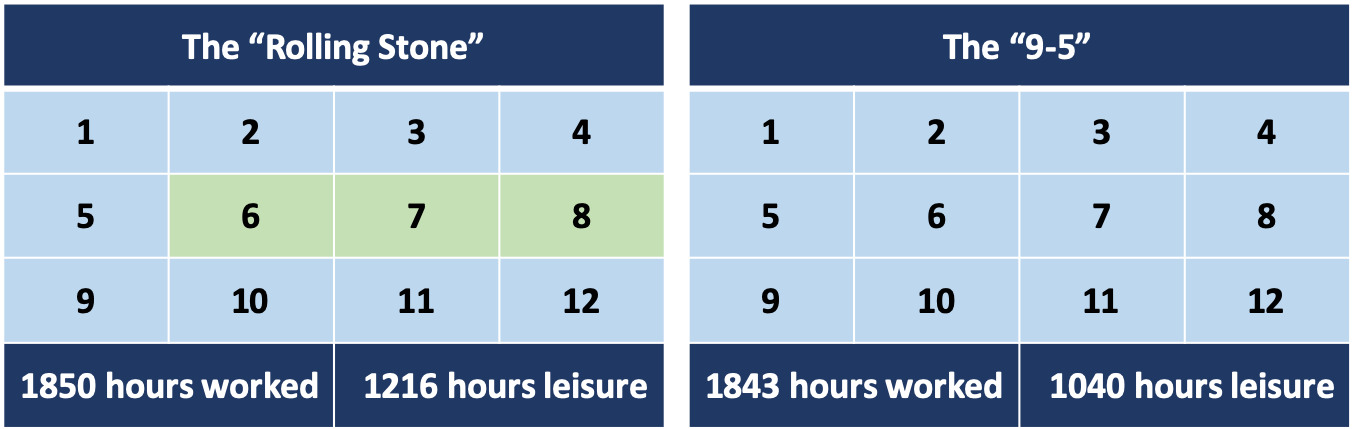

Using the Rolling Stone schedule, it’s possible to complete as much work in 9 months as everyone else gets done in a year. Instead of getting two days off a week, you would take a brief break to recharge every few weeks. Here is what it might look like:

Using this schedule you actually get more hours of productive work in addition to more leisure time. This result seems too good to be true, but the missing numbers come from reducing the amount of transition days that are not quite work and not quite leisure. Monday mornings are not fun, and this is a way to get rid of them.

If you’re wondering how this would work in reality, consider how movies are made. Groups of people come together to accomplish a shared goal, even living in trailers to minimize distractions. These sessions are intense, but create enormous value by compounding the momentum that the team creates while filming. As an example, Lost In Translation (2003) was filmed in 27 days, with many scenes shot around the clock since the hotel wouldn't let them film during the day. It grossed $119M on a budget of $4M, a 30x return.

The schedule above also resembles that of a professional athlete. Your “season” is during the 9 months you are sprinting, while offseason is the extended leisure time.

The Rolling Stone example is an extreme version of this, but provides an interesting observation: with the right strategy, it’s possible to increase both productive time and leisure time. You don’t need to be a baseball player to adapt this schedule into your own life. Simply being mindful of when you are switching from work to leisure will increase the amount of time you have for both throughout the year.

📊 Charts

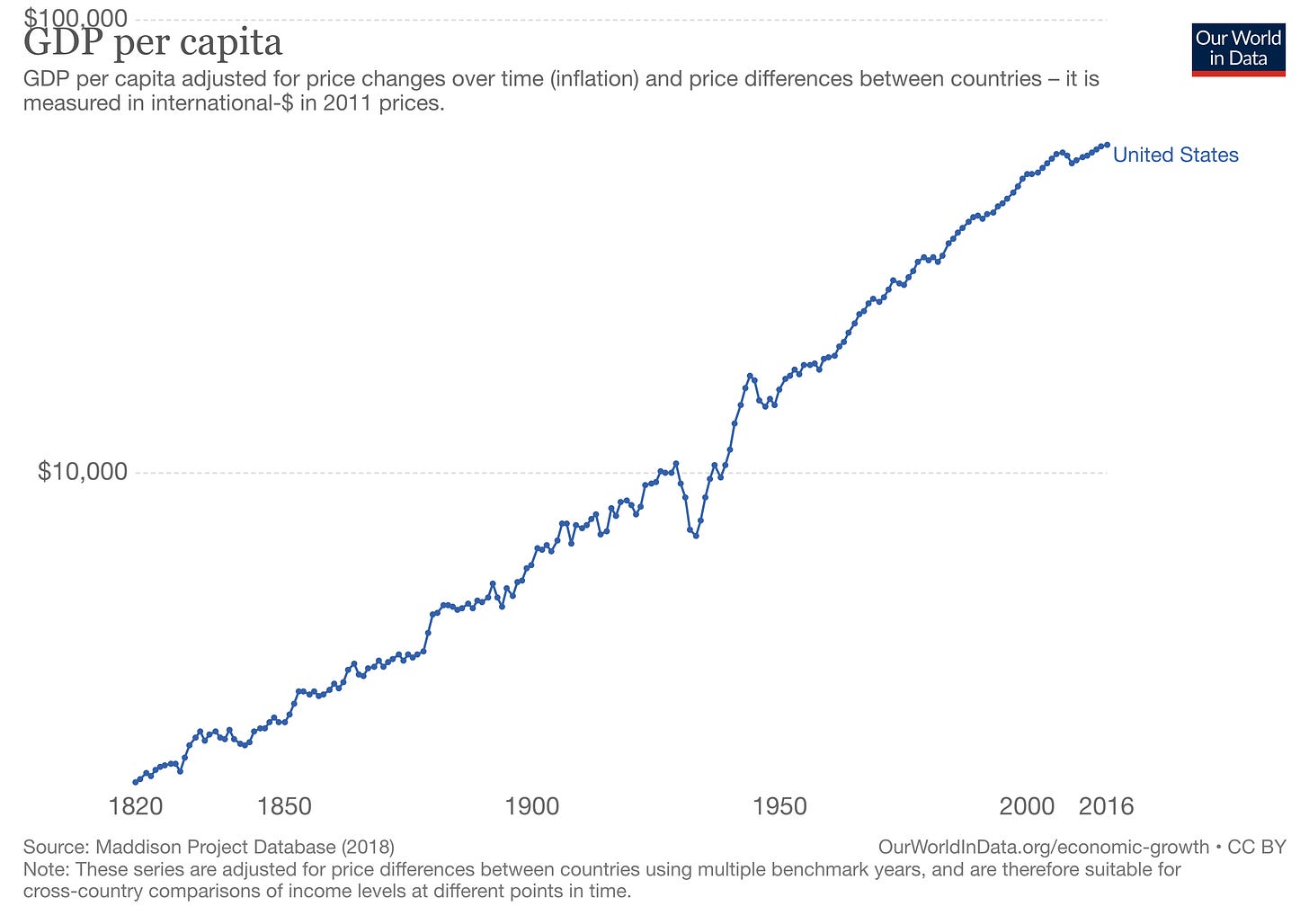

A picture is worth a thousand words, and this section curates the best infographics and charts that tell a story about our world. This week, the topic is economic growth.

I only have one chart for you this week: the growth of the United States GDP adjusted for inflation. Remarkably, this number has risen at an incredibly stable rate for over 200 years. What is going on here that is fueling this growth, and why is it so constant?

⬇️ Follow me on Twitter and Medium.

Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that summarizes my findings from the week in technology. It's part soapbox, part informative. It's free, you’re reading it right now, and you can subscribe by clicking the link below 👇