Nurturing Curiosity

What are the most promising strategies for someone looking to nurture intellectual curiosity?

I’ve been thinking more about 'amateur experts’, and what it takes to achieve the rate of growth necessary to become one. One of my favorite definitions for this comes from Niels Bohr, who described an expert as “a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field.” A corollary to this statement is: becoming an expert requires applied curiosity over a long enough time period to make those mistakes. Without curiosity, it’s simply too difficult to keep going without giving up. This essay attempts to answer the question: what are the most promising strategies for someone looking to nurture intellectual curiosity?

Be Honest

Curiosity seems to be strongest in areas where you have a personal connection to the topic. This is why we often see people diagnosed with some rare illness become experts overnight: they are driven by a personal desire to learn everything, even if they don’t follow a conventional path. In a commencement speech at Stanford University, Steve Jobs called this “connecting the dots” — it’s the process of linking your past experiences in a way that creates new ideas.

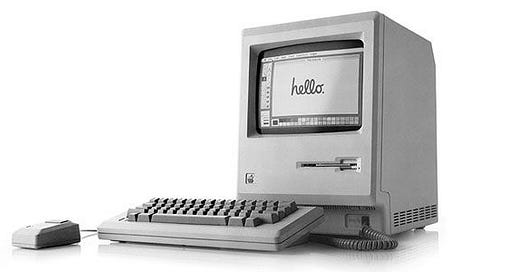

Steve’s story is simple: after dropping out of college, he would sit in on classes that genuinely interested him. As it happened, he sat in on a calligraphy class that covered the basics of fonts and design. Years later, the lessons learned from that class became a driving force in shipping the Macintosh computer with a palette of beautiful font options. Every Word processor today takes this feature for granted, but at the time it was a unique combination of seemingly unrelated interests.

This example seems like a random chance, but it is actually the result of a very powerful force: recombination. Very simply, recombination is the number of different possible combinations of a set of ideas. It’s why so many startups say they are the “Uber for X” or the “Airbnb for Y”. These descriptions seem trite, but actually take advantage of a strong fundamental truth: the number of ways that different ideas can be combined is a very large number, and what has proven to work in one field may translate well to another. Recombination is the reason why no two deck of cards have ever been shuffled exactly the same way twice. The number of ideas in the world is much larger than the number of cards in a deck, but they require people to shuffle new combinations to find the ones that work.

Does that mean you should try to find a successful idea by copying something from another field? Not necessarily. Remember, one of the key factors for genuine curiosity is a personal connection to the topic. When Steve dropped in on the calligraphy class, he wasn’t thinking about how it would end up benefitting some future business endeavor. He did it because it was interesting, and was able to connect the dots down the road.

This type of exploring is difficult, because it can seem unjustified to others. You’ll get questions like “why are you wasting your time on that?”. If you need permission to explore something that interests you, consider this your sign: explore something for no reason other than to satisfy your curiosity, and don’t worry about how it will be of use. If you’re being honest about exploring something for your own curiosity, then you’ll be pleasantly surprised with the number of new areas you can apply it to. This is doubly true for niche topics that haven’t been explored. If you’re playing with a different deck, you have a better chance of coming upon some combination of ideas that are brand new to the world.

Cultivate Friendships

Curiosity is difficult to develop by yourself. With the exception of a few isolated examples, most new ideas were explored by groups of people. Einstein would take walks during lunch with his friend Michele Besso to discuss his progress on the theory of relativity. During one conversation, he ran home to scribble an idea that had come about as a result of their daily jaunt. The last line of Einstein’s famous Special Relativity paper pays tribute to this relationship, stating:

“In conclusion, let me note that my friend and colleague M. Besso steadfastly stood by me in my work on the problem here discussed, and that I am indebted to him for many a valuable suggestion.”

There are simply too many combinations of ideas for an individual to meaningfully explore during their lives. History romanticizes the isolated genius, but collaboration and an open exchange of ideas are important for the creative process. Talking with others is still the best way to expose yourself to different ideas that you haven’t considered yet.

Until recently, these conversations were limited to mainstream ideas. It was simply too difficult to find a critical mass of others who were interested in niche topics. The internet has changed that. With over 5 billion people online and growing, it’s practically guaranteed that there is a community available for whatever topic you can think of. This is important because it means we’ve unlocked one of the biggest constraints on new ideas: communicating cheaply with others.

There is still a stigma that you can’t make “real friends” online. Knowing that meaningful connections can be made online is one of the biggest secrets I believe to be true about the world that most people don’t agree with. Myself and many others grew up with the internet shaping a large part of our social development. I’ve made both acquaintances and deep friendships with people whom I’ve only interacted with digitally. Anyone who plays computer games or frequents Internet forums will tell you that the influence of these friends is no less real than the people who you meet offline through work, school, or hobbies.

The transition from online friendships to offline ideas is still difficult, mostly because it’s been neglected by the companies that make those connections. By now it’s clear that going the other way, friending people from the offline world on Facebook, has become a multi-billion dollar business. Since it’s difficult to monetize offline social capital with advertisements, there’s still a lot of work to do here. Meeting in person is still one of the best ways to solidify a bond, and until that experience can be replicated online, it will take dedicated effort to cultivate online relationships. Effectively finding, maintaining, and nurturing online relationships is one of the greatest advantages that a person can have today.

Capture Ideas

Simply looking for new combinations of ideas will yield a surprising amount of novelty. I’m not sure why more people don’t do this. There seems to be a common misconception that inventing new things is reserved for a special kind of person or requires a degree of some sort. I’m happy to report that anyone can come up with new ideas — your unique life experiences, knowledge, and interests create a deck of ideas that will yield different combinations that anyone else.

Fortunately, this is a skill that can be trained.

One of the best ways to recognize new ideas is to simply write them down when they appear to you. I believe that writing is key to solidifying the mess of thoughts, emotions, and general clutter that fills up our mind on a daily basis. I’ve talked about my process for writing before, and would emphasize that it doesn’t have to be a formal exercise. Keep a note open on your phone where you jot down things as they occur to you. If you find yourself coming back to a specific idea over and over again, you’ll know it’s worth investigating further.

Building this habit — writing down ideas, comparing them against each other, returning to your list frequently — will reinforce the process so it becomes something you do without thinking. If you’ve ever caught yourself mindlessly shuffling a deck of cards over and over again, this is like that. It should work like a background process that runs with little to no conscious thought to “switch” into idea mode. Work hard to integrate this type of behavior into your daily routine for two weeks, even if you don’t have any “good” ideas that day. Simply opening the list and scanning previous entries will help to kickstart the process. Soon, you’ll find yourself noticing all sorts of surprising connections that previously went unnoticed.

There is at least one other technique for capturing ideas that’s worth mentioning: building models. Models are frameworks that you can use to understand how a system works. Once I find a good model, I try to apply it to all sorts of areas of my life. This helps me predict how things will turn out and can simplify complicated situations.

One of my favorite examples of this type of framework is a decision model. If you’ve ever used a list of pros and cons to help with a decision, then you are familiar with this. Models are helpful because they let you layer your thinking, instead of needing to keep everything in your head. For example, maybe you want to decide if you should return to graduate school. You might make a list that looks like this:

Based on this analysis, you may be tempted to think that graduate school is the right decision. However, you can go one step further and apply weights to these criteria based on how important they are to you.

Let’s imagine that you assign each criteria a score of 1-5, with 5 being the most important. Perhaps you are comfortable in your current career, and it’s very important that you stay near your family. Now your list looks like this:

This very simple model helps to highlight the fact that writing things down lets us build complexity in a way that is difficult to capture in our heads. This in turn makes it easier to explain to other people, who tend to pick things up more quickly if you can simplify the concepts. Just because something seemed complex before you figured it out doesn’t mean there isn’t a simple, intuitive explanation for others.

Decision models are helpful for evaluating options, but break down when trying to factor in how other people may act. For dealing with people, agent-based models are my go-to. Agent-based models predict how people will act in a given situation. Similar to our pros/cons list, these models can have different levels of sophistication. You might assume that people will follow certain rules in a given situation, or maybe people have certain biases that impact their decision making. By cataloging known biases, you’ll develop a useful heuristic for predicting outcomes. People are complex, but these can give helpful approximations for real behavior.

A well-known and common bias is that people generally have a bad sense of judgement about things that will occur far in the future. We call this effect hyperbolic discounting, and it is the reason for all sorts of short-term decision making. If I were to offer you $10 today, or $11 tomorrow, you may be tempted to just take the $10 today. However, if I were to say that I will give you $10 in a year, or $11 in a year and a day, you would probably opt for the $11. After all, what’s another day when you’ve already waited a year?

You can generally assume that people will choose a smaller, immediate reward over some larger reward in the future. If people were rational, it wouldn’t matter if the time between the reward was today, tomorrow, or next week. This bias, along with many others, is just a small demonstration of the predictive powers of agent-based models. For a complete list of common biases, I highly recommend Nobel Prize winning economist Daniel Kahneman’s book: Thinking, Fast and Slow.

When trying to predict how someone will act, ask yourself: am I applying a rule based prediction (Bob always acts in this way, and he will do so again this time), a behavior based prediction (Alice has a known bias on this topic, and a high likelihood of it affecting her decision), or a rational based prediction (John wants to achieve x, and the best way to achieve x is to do y, therefore he will do y).

When you have a new idea, try to fit it into different models of how it might work to see if one fits. If you find that your new understanding fits into an existing model, then use that description to help familiarize others with your new insight. Remember “Airbnb for X”? This description isn’t necessarily a bad thing, especially if it helps people grok what you are saying.

The ability to communicate curiosity in a way that is accessible is a reinforcing pattern: the more people that also find your idea interesting will drive down the perceived risk of exploring it. This makes your niche bigger, and increases the value of ideas within it.

Build Your Environment

Certain environments are much better than others for developing new ideas, and these can be manufactured to some extent.

The ideal environment for curiosity is probably something like graduate school, but without the grant applications and bureaucracy. What works well to corral PhD candidates is a blend of publishing deadlines, advice and direction, and a community of like-minded colleagues. These three pillars are key to creating a curious environment.

Obviously, you don’t need to be in a university to discover new ideas. Einstein developed relativity while working as a patent clerk, after being rejected from most universities in Europe. He recreated the environment from university in his own way: the deadlines, advice, and colleagues were replaced by his friends and pen-pals whom he exchanged letters with.

Consider the content of Einstein’s letter to his friend and colleague Conrad Habicht:

So, what are you up to, you frozen whale, you smoked, dried, canned piece of soul…? Why have you still not sent me your dissertation? Don’t you know that I am one of the 1.5 fellows who would read it with interest and pleasure, you wretched man? I promise you four papers in return. The first deals with radiation and the energy properties of light and is very revolutionary, as you will see if you send me your work first. The second paper is a determination of the true size of atoms…The third proves that bodies on the order of magnitude 1/1000 mm, suspended in liquids, must already produce an observable, random motion that is produced by thermal motion. Such movement of suspended bodies has actually been observed by physiologists, who call it Brownian motion. The fourth paper is only a rough draft at this point, and is an electrodynamics of moving bodies which employs a modification of the theory of space and time.

In this brief letter are all of the ingredients necessary for a thriving environment:

Community (and the time honored tradition of name calling shared only by true friends)

Commitment to a deadline (“I promise you four papers in return”)

Advice and direction (“Don’t you know I am one […] who would read it with interest and pleasure”)

We can do much better than this today. The phone in your pocket gives you access to a community of colleagues in whatever topic you’d like. The improvement of translation tools means that they don’t even need to speak the same language as you to have a productive discussion. The mistake most people make is thinking that the environment needs moss-covered buildings or an expensive lab to fit the bill. Those things help justify expensive tuitions, but don’t fundamentally affect the quality of the ideas. Building a curious environment is a product of the people, rather than the place. This is why the group in Los Alamos was able to create the atomic bomb: they had everyone they needed and were able to communicate cheaply and instantly. If an unknown desert town in New Mexico isn’t a showstopper for a project as complex as nuclear weapons, then your kitchen table is probably fine to get started on your work.

Community can be recreated online, and in fact is probably better than the physical model we operate with today. Since most of the people are online, it follows that your environment should be also. We’ve established that one of the three pillars of a curious environment, community, can be recreated online. What about the advice and deadlines?

People love to give advice, and simply signaling that you’re working on some problem is enough to attract others who may be able to help. Choosing an independent research direction requires more effort than having your advisor do it for you, but it can be done. Creating a well-documented and up-to-date personal website or social media presence is cheap and effective. Make it clear that you’re open to feedback, and prominently display contact information across your environment. Assume that someone will only find the least documented page you have, and make that your baseline for communicating who you are and what you’re working on.

Deadlines are a good thing. Work tends to expand and contract based on the amount of time you have to complete it. Setting achievable, but overly ambitious deadlines is what will force you to just get the thing done, rather than endlessly tinkering. The only reason I write every week is because I know that all of you on the other side of the page expect to receive content. Without the cadence of publishing, I would let things that are urgent, but unimportant, get in the way of creating.

Setting a deadline is easiest when you have someone who will hold you accountable. Make your schedule public, or commit to something financially in order to incentivize yourself. This can be as simple as sending the following email to a friend or colleague: “I am interested in x, and plan to explore it over the next few weeks. I’m going to write up what I find and publish y by this date -- can I send it to you when I’m done for your feedback?”

If you don’t have a specific person to share it with, then use social media as your platform. Here’s a free startup idea: create a way for people to publicly commit to donating to charity, unless they accomplish a verifiable result by a certain date. Only release the funds once the author responds with a published URL pointing to the deliverable.

Conferences are a great forcing function for publishing papers, but they shouldn’t have a monopoly on intellectual content creation. The current paper review process for conferences is more administratively complex than needed. Borrow the good parts by committing to a deadline, and publish freely without the hassle of a burdensome submission process.

Of course, people don’t just publish papers and pay tuition for the environment. The credential, the brand of the university and prestige, gives your work legitimacy that is difficult to recreate independently. However, it’s not a lost cause. The value of being associated with a university is not for your benefit, but instead for people in the future who need to evaluate your credibility. Universities sell insurance – they limit the exposure that hiring managers or investors have by removing some of the burden of due diligence. Recreating this signal is hard, but luckily, it’s aligned with your goal: producing great work.

By concentrating your efforts on creating ideas and content that people want, you are creating a credential that is self-evident. Humans value reputation above all else, so identify the three people in your topic area whose opinions matter most, and have them review your work. Get them to endorse your mission by giving them a piece of the upside: either through equity or association. If your work is good, then they will benefit from being associated with you early, while you were still unproven. This will solidify their reputation as an expert, and provide more opportunities for them in the future.

We apply credentials broadly, but it’s more impactful to know who is endorsing your work, rather than where it was done. These types of apprenticeships used to be common, but have mostly fallen out of favor due to the institutionalization of academics. If a professor decides to leave, the university doesn’t want the reputational benefits they accrued to go with them. Alumni are the lifeblood of universities, and keeping them affiliated by gatekeeping credentials is a fundamental aspect of the university business model.

By separating credentials from environment, you’ll reinforce your reputation and build a network of curious, ambitious people who share your interests. This will take more effort than simply getting a degree, but your time will be spent creating, rather than administering, your credential.

If you’ve gotten this far, it’s likely that you have some idea that’s been nagging at you. Maybe you’ve been avoiding looking straight at it, for fear that too much attention will extinguish the possibility of it working. Very often we find ourselves preferring to leave our dreams in idea-land, where they are safe from the scrutiny of others. If that’s the case, consider dusting off the idea and exposing the rough edges — it may just turn out to be the dot thats been waiting to be connected.

One of the best numbers to optimize for early in a project’s life is number of days in a row that you make progress. If you’ve ever started a fire, this is like that. You don’t just throw all of the wood on the pile at first: you start with kindling and a small flame, and keep feeding it fuel until it’s roaring. If you try to add the big logs first, you’ll extinguish your fire before it has a chance to start. With your idea, start small. Turn it over in your mind until you know all of the facets. Share it with others, and don’t be afraid to adapt based on new information. Remember — the number of idea combinations is vastly bigger than you can imagine. The only way to discover them is to start shuffling.

If you enjoyed this essay, please consider sharing it with a friend. Sunday Scaries doesn’t have paid subscriptions yet, so the best way to help support this publication is to spread the word.

Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that answers simple questions with surprising answers. It's part soapbox, part informative. It's free, you’re reading it right now, and you can subscribe by clicking the link below 👇

Credits: Photo by Yifeng Lu on Unsplash, Photo by Jack Hamilton on Unsplash