Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that explores simple questions with surprising answers. I usually send it on Mondays, but I am experimenting with a twice a week format. If you prefer this publication cadence, let me know by replying directly to this email. Sunday Scaries doesn't have paid subscriptions yet, so the best way to help support this publication is to spread the word. You can do this by forwarding this email to a friend or sharing it on social media.

An interesting result of the next few months will be the slow shift of individual preferences. We're going to remember what we like instead of what the crowd expects us to like. This divergence in personal taste isn't social distancing -- it's social drifting.

Individuality is tough to maintain when you're on the same schedule as everyone else. Working in the same office builds a shared culture, but it also smooths over any rough edges that result from bringing different people together. People tend to conform when their personal preference causes an inconvenience for the group. It’s the reason why the guy with the strict diet always gets to pick the place for lunch. Unless you feel strongly about a decision, you’re more likely to give in to what the group wants.

These small differences add up. Throughout the day, we are continually making compromises between what we would prefer to do and what is expected as a cultural norm. Social distancing means that our quirks will begin taking over these norms. When we finally come back together our group cohesion will look like a melting ice sculpture: a similar shape with smudged details.

What we think of as our personal preferences are not ours — they are the result of social forces acting on us, day after day. Social distancing will cause these preferences to drift and will end up in an equilibrium that is closer to our actual individual ideals.

When we come back together, we may be surprised to find that we do not quickly fall back into our same social circles. Even if our individual preferences change only slightly, we will see this effect having a significant impact on who we spend time with.

A simple example should help to illustrate this point.

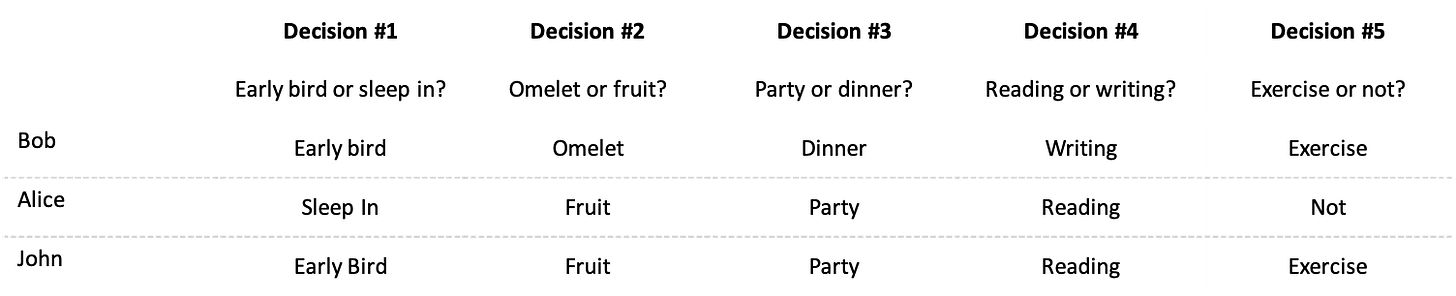

Consider your preferences by asking how you would like to spend your ideal day. Answers to this question will vary wildly from person to person, yet most of us are not living this idealized existence. In this example, there may be five main components to your ideal day: what time you wake up, what you eat for breakfast, how you choose to socialize, what you do for leisure, and whether you choose to exercise.

Even if each component had only two options (e.g. wake up early or sleep in, exercise or not), this still gives us dozens of ways to spend a perfect day. Everyone will have different combinations based on what is important to them. Maybe you like to wake up early and go for a run, or perhaps you'd prefer to sleep in and enjoy the morning. Ask three people this question, and you'll get very different answers.

However, the world doesn't work this way. Others influence our individual preferences. Maybe Alice and John want to spend their day together but can't decide when to set the alarm in the morning. In most cases, one of them will be willing to change their preference to make the situation work.

This effect happens to us every day. Instead of five basic decisions with two options, we make hundreds of small choices with subtle variations. We handle these by reverting to the mean for most decisions and doubling down on the few choices that are most important to us.

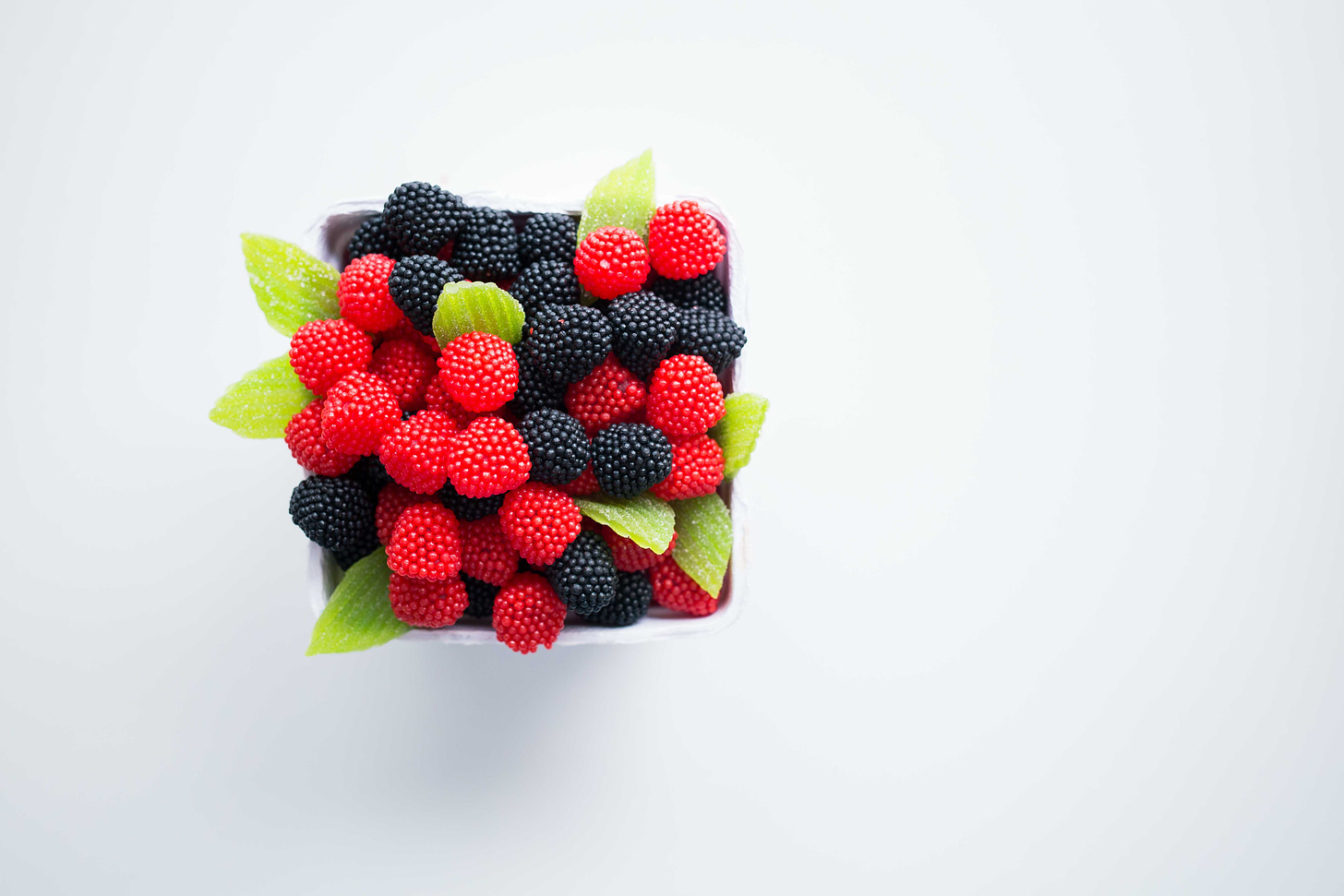

What we are going to experience over the next few months is a sudden removal of the pressures to change our individual preferences. It may not occur to us at first — maybe we've forgotten that we prefer to sleep in because we've been waking up early for so long. Maybe our 5 o'clock exercise class was done out of convenience, but we would much rather go for that mid-afternoon run to clear our minds. We're eating omelets when we would prefer fruit. Without someone to order our food for us, we might just rediscover our taste.

This realization will occur to each of us in different ways, but the result will be the same: the erosion of the small coordination games that we play, replaced by our personal preferences. We're used to being around people that are just like us, because we've agreed on what the normal behavior is for most scenarios. This collective illusion needs constant reinforcement. Otherwise, it begins to break down.

When we come back together, we may look around to realize that our friends and colleagues have new hobbies and tastes that don't match our own. We should celebrate these differences. Understanding our personal preferences will be a benefit of the time spent alone. Not everything will shift — certain cultural norms run deep enough to resist a short break from society. The ones that do will likely be preferences that existed just under the surface, and were waiting for a change of perspective to bring themselves to your attention.

In some cases, the shift may be drastic enough that our social groups change entirely. If you're unwilling to relinquish your new preferences to conform to your previous environment, it will mean finding people with the same tastes that you've rediscovered.

We tend to segregate ourselves into groups that define most of our habits. We prefer for people around us to be the same, so we can distinguish other groups by the ways that they differ. Groups tend to form around a few key similarities and are more flexible on other factors. Any other situation results in too much friction to remain in a dissimilar group.

This is fine too, and may help to explain some of the malaise that we will feel when we first come back together. People will seem quirky and not so ready to give up the individual freedoms that they've gotten used to.

The next few months are going to be a giant social experiment. Understanding that some of our tastes are the result of social pressure, rather than our preferences, may give us the ability to critically examine what's working and what's not. If you're eating an omelet out of convenience, do yourself a favor and try the fruit. You might find that you enjoy it.

If you enjoyed this essay, please consider sharing it with a friend. Sunday Scaries doesn't have paid subscriptions yet, so the best way to help support this publication is to spread the word.

Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that explores simple questions with surprising answers. It's part soapbox, part informative. It's free, you're reading it right now, and you can subscribe by clicking the link below. 👇

Photo by Brooke Lark on Unsplash