Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that explores simple questions with surprising answers. Sunday Scaries doesn’t have paid subscriptions yet, so the best way to help support this publication is to spread the word. You can do this by forwarding this email to a friend or sharing on social media.

One of the first independent decisions that teenagers make is the choice to attend college. College provides one of the best environments for social development that we offer as a society. Unfortunately, we don’t manage the transition out of this experience very well.

If I were to graph the number of friendships I've held throughout my life, there would be a shocking drop-off around the time I graduated from college. Within just a few years, I’d lost contact with most of the connections I made as an undergraduate. When I asked people about this, the common response was to say that these must not have been "real friends". After all, if these were actually my friends, I would have kept up with them.

This argument misses the point. Why should we only be able to maintain friendships with a close few? It’s clearly possible to support a diverse network, since we do it for the first twenty-odd years of our life. Yet, once our education is complete we’re expected to rebuild our friendships from scratch.

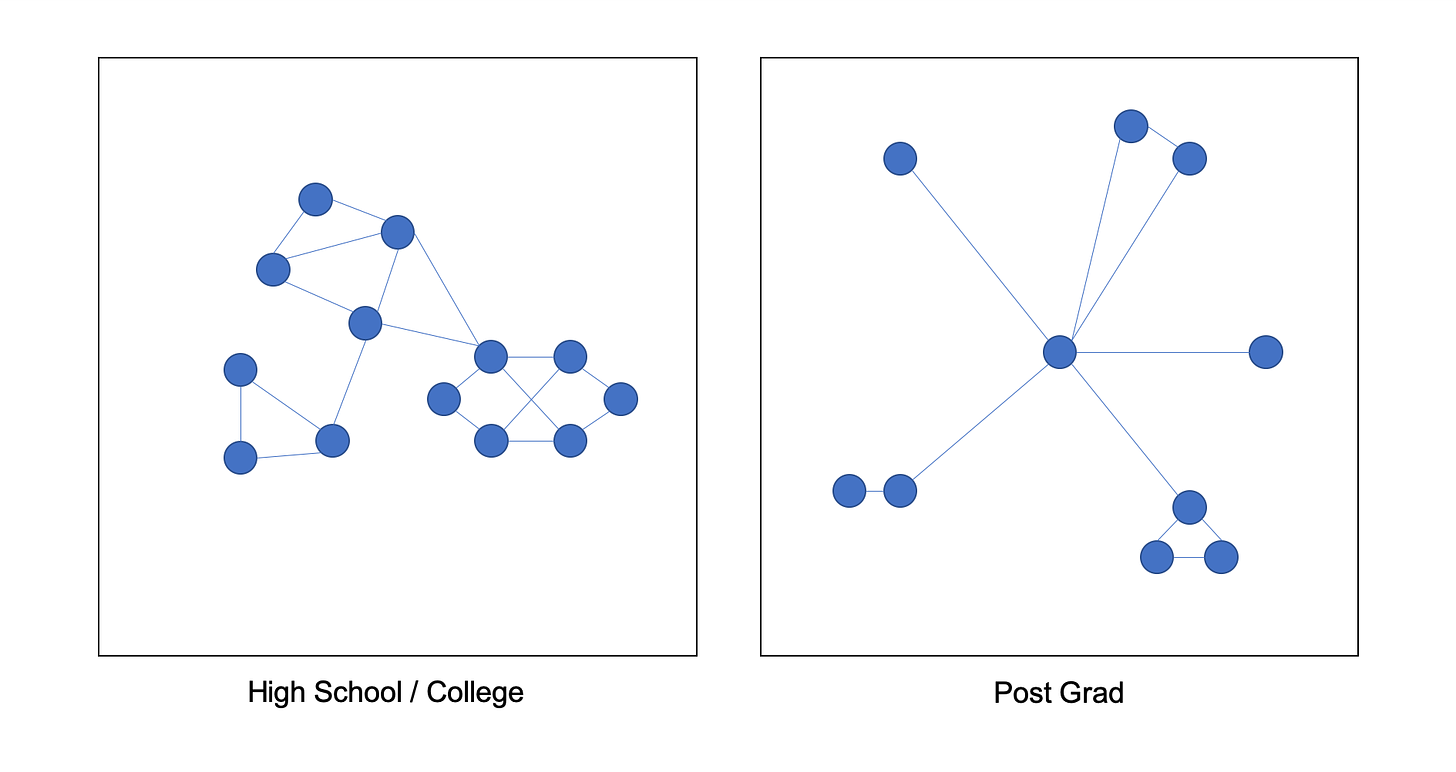

When I reflect on my early twenties, I’m struck by how quickly my social circles changed. Not only did I have fewer connections after graduating, but the shape of my network looked completely different. Instead of being involved in a large community where everyone was connected, I found myself at the center of a wheel, with spokes radiating out in every direction. For the first time in my life I was meeting new people, but none of them knew each other. This felt like a big change, and I struggled to understand what was happening.

I believe that this change affects young adults more strongly than we realize. The truth is that loneliness continues to rise. It’s now so common that we’ve stopped paying attention.

The same people who told me that I should only focus on my real friends assured me that this happens to everyone. Since it happens to everyone, it can't be so bad.

Can it?

By this logic, no one should have quit smoking cigarettes. Just a few decades ago, cigarettes were everywhere -- try finding a popular film from the 1960s without someone lighting up. This doesn't mean cigarettes weren't harmful. It just means we didn't have a good way to measure the alternative. Since everyone was doing it, finding a control group meant going against years of tradition. Eventually we realized that cigarettes were killing us, but the damage was done.

Young adults today are experiencing a similar phenomenon. We flood cities after graduation and dive headfirst into our new careers. Saddled with student debt and a comparison culture, finding a job seems like the obvious next step in the game. We’re lighting up, and there is no Surgeon General’s warning to tell us otherwise.

This disconnect is stronger than ever before. A successful career is no longer spent at a single company, or even a single city. Employees are expected to change jobs to maintain a competitive salary. As colleagues come and go, our social ties continue to break down. Even if you are not someone who tends to job hop, it's likely that coworkers and friends will transition between careers and cities. There is little incentive to invest time into these relationships, since they are not guaranteed to last.

This raises two questions: why are friendships today so dependent on work and school, and how do we build stronger connections outside of the system?

Education is the core of our social development, and it's taken a very weird turn over the last 50 years. Despite rising costs, our educational outcomes have stayed flat since the 1970s. Attending a modern school doesn’t give you a better education, but it costs ten times as much.

What is going on?

American schooling is a chaotic jumble of seemingly unrelated activities. We're expected to learn, develop friendships, practice sports, and complete extracurriculars. The flurry of movement keeps children and their parents so busy that there is hardly time to ask: is this the right way to do it?

We're seeing millions of Americans ask this exact question as schools close during the ongoing lockdown. As parents help their children connect to Zoom lectures and college students complete online assignments, the reality of our system is setting in. School is not an education system -- it's a daycare.

Kids today are able to access premium education online for a fraction of the cost that we invest in our school systems. Like many fields, educational outcomes follow a power-law distribution. A few teachers are orders of magnitude better than the rest. Until recently, these teachers were limited by geography and the students they could physically interact with.

Today, these educators are available to everyone:

The best YouTube channel for math has over 3 million subscribers and hundreds of millions of views.

Richard Feynman's complete lectures on physics are available online, for free.

Khan Academy and Coursera provide thousands of topics with world-class educators.

I believe in the value of education — that’s why I know we need to fix it. The social benefits of school need to be separated from the educational objectives.

By putting them together we are failing at both. You wouldn’t want a gourmet meal put into a blender, no matter how good the ingredients are by themselves. We’re doing this with education and social development and it tastes just as bad as you would expect.

The extra money being poured into schools is not paying for better educational outcomes. It’s paying for the social amenities that we’ve come to expect from a college experience. Instead of effective teachers and modern curricula, we’re getting new sports stadiums. This investment provides a fantastic collegiate experience, but ends abruptly.

By the time college graduates enter the workforce, their entire social network is made up of people they’ve gone to school with. After graduation, we pull the rug out from underneath them and wonder why they fail to adapt.

Instead of relying on our academic system as a way to support social development, we should focus on building lifelong communities that are not tied to the status games of education and prestige. Universities are in the business of issuing credentials, which only remain valuable if they are scarce. Social networks benefit from long-term connections and actually grow in value as more people join. Since these two objectives are opposed, we’ll see better success by separating them.

This is painfully obvious to millions of Americans who are being forced to work and learn from home. Paying for tuition doesn’t seem so worth it when most of the things we learn can be found online for a fraction of the price. However, you’d be hard-pressed to find someone who is willing to forgo their college experience with a promise of online classes. For most, the value of college is not the education — it’s the network.

Until we’re able to separate learning outcomes from social development, we’ll continue to see poor performance in both. We’ve unbundled education by moving it online, but still haven’t created a substitute for the social experience of school. As more and more people turn to online education, the opportunity for an independent social institution will continue to rise.

If you enjoyed this essay, please consider sharing it with a friend. Sunday Scaries doesn’t have paid subscriptions yet, so the best way to help support this publication is to spread the word.

Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that explores simple questions with surprising answers. It's part soapbox, part informative. It's free, you’re reading it right now, and you can subscribe by clicking the link below 👇

Photo by Vasily Koloda on Unsplash