Urgency and Incentives

History tends to give credit to individuals rather than groups for innovative breakthroughs. Consider:

Bitcoin, developed by a mysterious figure named Satoshi Nakamoto

Evolution, discovered by Darwin on the remote islands of Galapagos

Calculus, invented by Newton and applied to the physics of our world

It’s easier to attribute these successes to a single person rather than a group of people working toward a common purpose. We prefer to think of individuals as inventors because it appeals to our sense of ego. These achievements, while spectacular, were only possible because of the work done to lay the foundations for a breakthrough.

When a wave crashes on the shore, we do not give individual droplets credit for their ferocity. We recognize that they are carried along by forces greater than themselves, and if one droplet is to touch the land first, then it is because this is the way that things are.

Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash

Each invention listed above happened at a moment in history when the conditions were ideal for that specific breakthrough:

Bitcoin is a combination of inventions that have been in development for decades: cryptography, consensus algorithms, and linked lists all existed as well-researched components. Satoshi was a gifted engineer, but his ability to combine existing principles was the true invention.

At the same time as Darwin’s research, a competing scientist named Alfred Russel Wallace was independently compiling research for a similar manuscript. Wallace and Darwin published theories of evolution simultaneously, although Darwin’s name is the one we remember.

Newton’s discovery was mired in controversy thanks to the work of a competing mathematician, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Leibniz and Newton are now considered to have arrived at the theory of calculus independently.

There’s a quote that sums up my thoughts on this:

If you want to go fast, go alone; but if you want to go far, go together.

I’ve been thinking about momentum, and how we undervalue it as a society. Momentum compounds the rate at which we make progress in important areas. It’s helpful to focus on your momentum, but the real magic happens when we discover ways of making large groups work together in ways that compound progress. We can’t predict who will be the individual that makes the next discovery, but we can design systems that make the overall group move at a much faster pace.

There is plenty of literature on this topic, but I want to focus on two factors of momentum that I think are underutilized in modern society: urgency and incentives. By emphasizing these two factors, I believe that it is possible to organize groups to dramatically improve quality and execution.

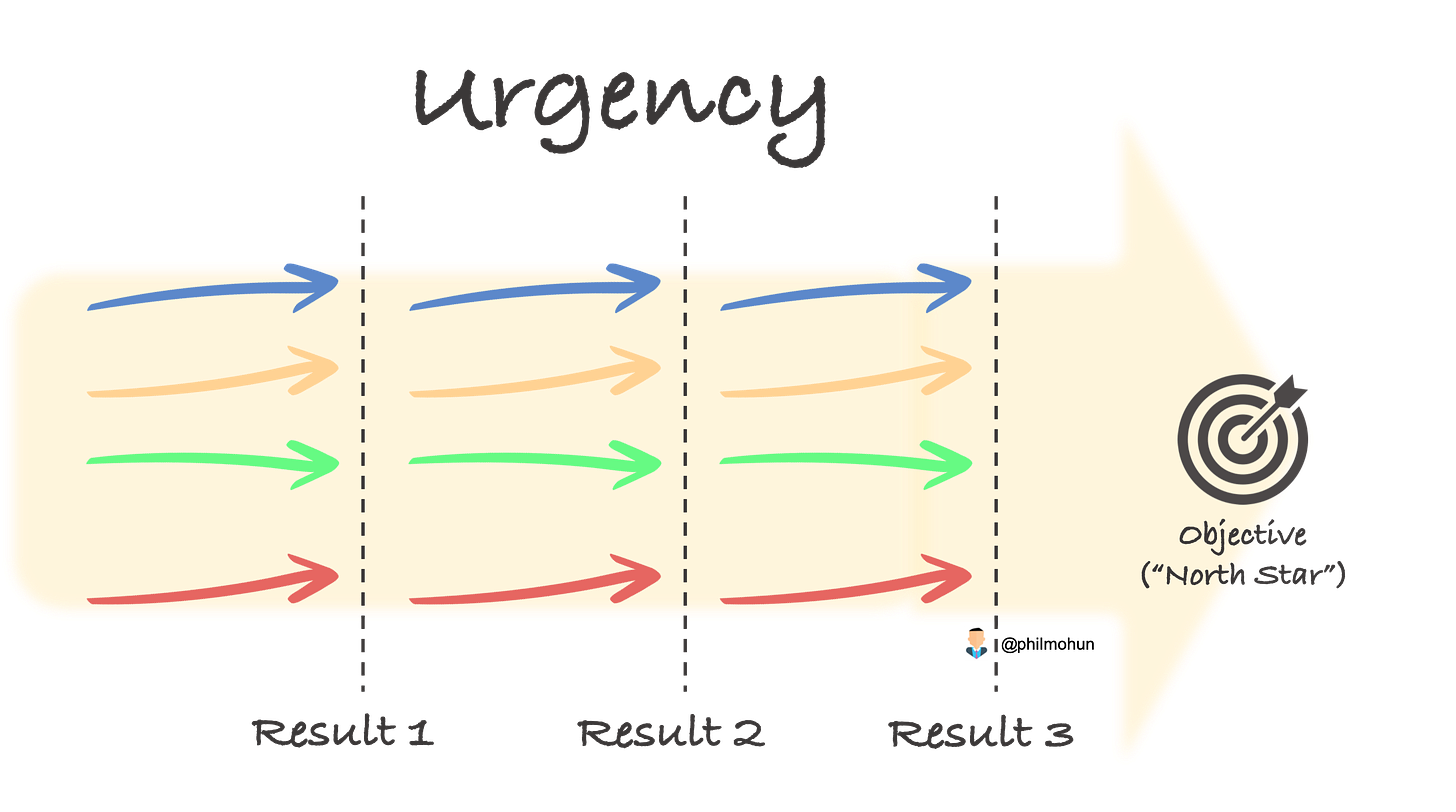

Urgency

If you’ve ever slept through an alarm, then you are intimately familiar with the benefits of urgency. A strict and present expiration date is incredibly effective at focusing the mind on the task at hand. These brief periods of stress are helpful, because they force you to make tradeoffs immediately for non-critical decisions.

Urgency for groups is no different. Whenever possible, teams should be working towards a deadline that makes them feel slightly uncomfortable. Unless it poses a safety or health risk, these deadlines act as a pruning mechanism for the bullshit that inevitably crops up whenever groups of people work together.

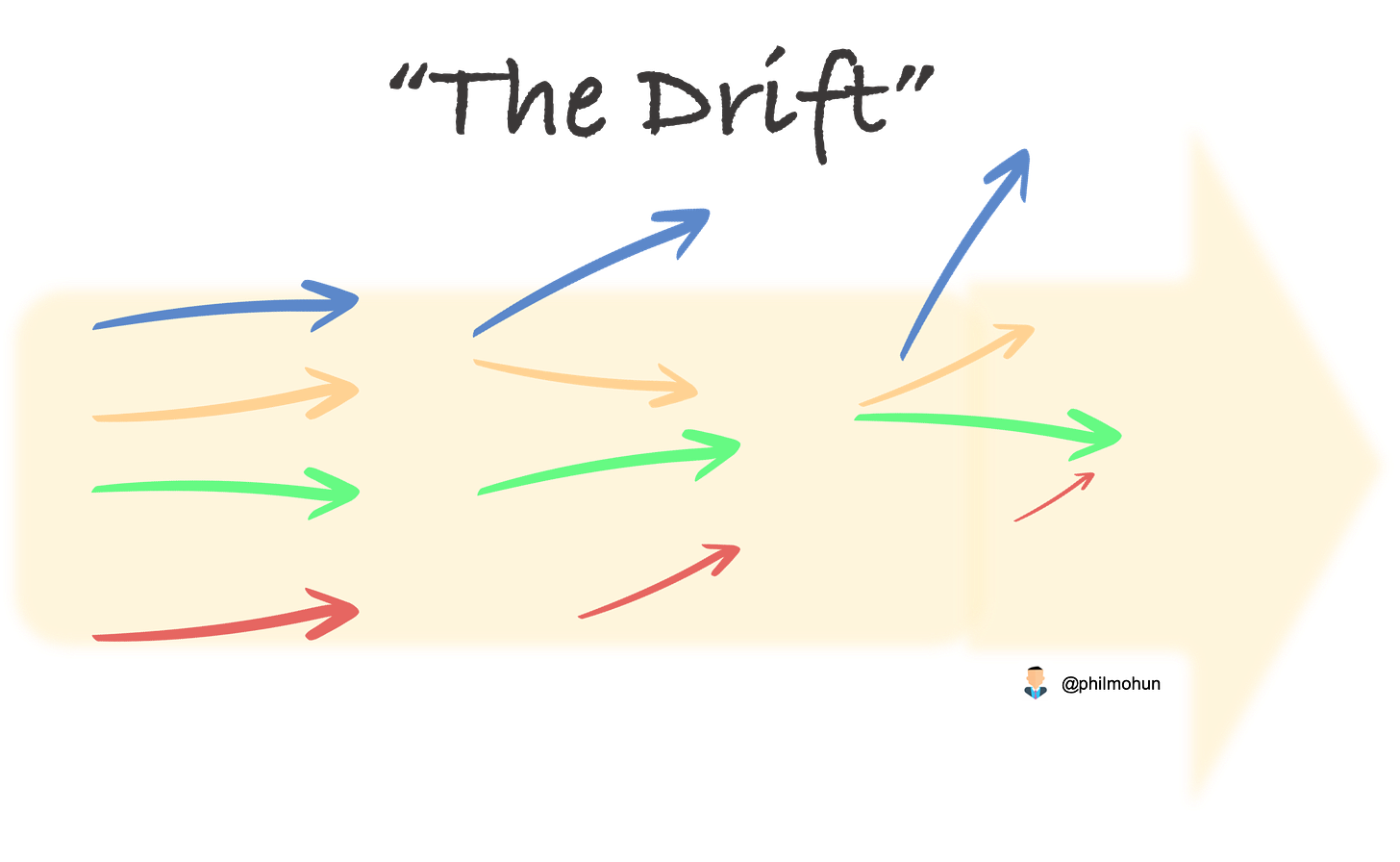

When projects are allowed to drift along without urgency, people tend to lose focus. A group may be highly aligned at the beginning of a project but will quickly find itself drifting as individuals begin to reprioritize.

This drift can be countered by using deadlines and clear objectives with measurable results. These objectives should be ambitious, but achievable within the capabilities of the group. Results need to feel as though they are within reach, rather than being vague or in the distant future. A good result is one that can be independently verified and marked as either completed or not. Ambiguous results that leave room for interpretation will fall to the lowest common denominator.

There are two ways to apply urgency to a project: you can impose it on yourself, or you can have it imposed upon you.

Self-imposed urgency

Self-imposed urgency can be an excellent way to quickly accelerate the pace of a project. In a famous example popularized by Ben Horowitz, the executive team at LoudCloud used self-imposed deadlines to create a situation that allowed them to sell their company for a valuation multiple that would not have otherwise happened. They created a deadline for the sale of their company that reached a fever pitch when EDS bought most of LoudCloud’s assets for $63.5M. Ben’s book, The Hard Thing About Hard Things, covers this lesson in great detail and is well worth a read.

Another example of self-imposed urgency from the technology industry is the launch of Amazon Prime in 2005. At the time, Prime was not a sure bet and posed serious risks to the stability of the site during the Christmas season. Despite this, Bezos insisted on shipping the first version of Prime within six weeks.

From a testimonial of the team involved:

We were originally given four weeks. ...

We said, “There’s no way we can build this in four weeks. Even if everyone worked nonstop, the minimum to do a minimum viable product was six weeks.”

The deadline for this project was the Q4 earnings call. Engineers were poached from their projects throughout the company and the team spent the next few weeks furiously designing and implementing the MVP. Bezos introduced the product right on schedule, and the team took some well deserved time to recuperate.

These types of deadlines can seem harsh. After all, there was no obligation to launch Prime during the busiest season of the year. Yet, the team involved cites Prime as one of their proudest accomplishments during their time at Amazon. People are willing to work hard if given the chance, and deadlines can motivate teams to work together and produce exceptional results.

External urgency

We are not always able to choose our timelines. In a recent example of this, China has reacted with swift and decisive engineering to build a massive hospital to contain the growing victims of the 2019-nCoV (Corona Virus).

The infrastructure needed to support this type of construction on such a short timeline is seriously impressive. China’s powerful central government gives it the ability to take action when presented with a fast-moving situation like an epidemic.

Built in just under two weeks, the hospital contains state of the art quarantine features including food trays, negative pressure design, and one-way doors to prevent the virus from spreading.

The urgency demonstrated by the government in responding to this threat has been impressive. Whether it will be enough to stop the spread of the virus remains to be seen, but it demonstrates the power of a dedicated workforce with a clear goal and timeline.

Incentives

Urgency without reward can lead to burnout. Many people gain satisfaction from work, but financial incentives remain a powerful motivator. This is why I believe the capitalization table is one of the best tools that we have to encourage momentum within projects.

A capitalization table, or cap table, is a ledger that tracks the equity distribution and ownership of a particular company. By providing people with meaningful equity in exchange for work, it’s possible to align the incentives of a team in a way that reinforces management objectives.

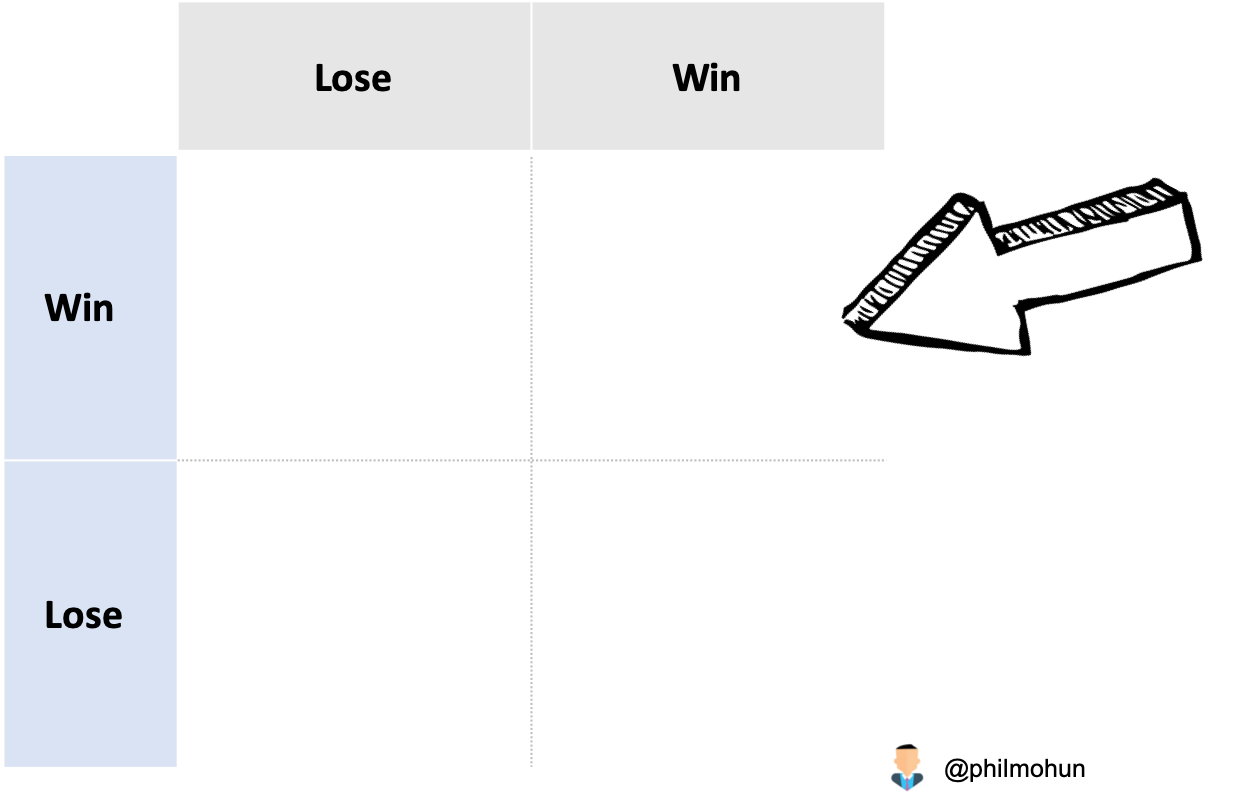

At its most basic level, the purpose of a cap table is to provide a solution to the Prisoner’s Dilemma. The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a classic game theory example that describes how two rational individuals may not choose to act in a way that maximizes their best interests. This could take the form of workplace politics that interfere with accomplishing the objective of a project.

By adding equity into the mix, it helps remove doubt from the equation as to what choices a worker should make. If the payoff from a successful exit is substantially higher than any particular project or promotion, workers will be more willing to set aside individual preferences to achieve the common goal.

This is a very powerful tool that has lead to much of the success seen in Silicon Valley, but has not been replicated across industries. For organizations with high growth potential, equity is one of the best ways to align incentives across participants over a long-time period.

Putting It Together

I believe that high levels of both individual and group momentum are key to achieving great results. Individual momentum can be dramatically improved simply by controlling your schedule to reduce task switching and stay “in-season.” This type of work has been popularized within sports and creative industries, but may have useful applications in other fields.

Group momentum is more difficult, since people who act rationally as individuals may not have those decisions aggregate in a way that maximizes results. To combat this, urgency should be applied to projects whenever possible to minimize drift across individual priorities. Urgency can appear in the form of frequent, repeating deadlines that build confidence in the team to accomplish specific tasks as a unit. Urgency for its own sake is an acceptable method, but can be overused if not complimented with periods of leisure and reward.

Incentives provide a guiding force behind the drumbeat of urgency. These should be awarded in the form of an equity option that pays-out for meeting specific results tied to the group’s collective success. This will reduce selfish behavior and keep everyone rowing in the same direction.

Together, these tactics can dramatically improve the momentum of both individuals and groups, creating compounding effects that grow more pronounced over time.

⬇️ Follow me on Twitter and Medium.

Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that summarizes my findings from the week in technology. It's part soapbox, part informative. It's free, you’re reading it right now, and you can subscribe by clicking the link below 👇