Why You Need A Captain's Log

During my first summer internship, my only job was to take notes and distribute them after the meeting. The fact that I had no idea what was going on in those meetings didn’t seem to be an issue.

I would file into the conference room, open my laptop, and begin typing away. My notes after the meeting were legible in the same way that a bowl of Alphabet Soup is legible. There were letters and words, but no substance.

The tendency to assign note-taking to the most junior member of the room creates a negative stigma about the whole process. Senior employees remember note-taking as a distasteful job for analysts. Junior employees can’t wait to be promoted so they can move onto more exciting tasks. This experience cements note-taking as something to grow out of, rather than a skill to improve. If you show promise as a note-taker, you are often rewarded with tedious project management and managing action items.

No wonder people hate it.

This cycle is unfortunate because note-taking is the most important form of communication that you do every day. When we think of communication, we typically think of talking or messaging with another person. Sending an email or a text causes it to instantly arrive in someone else’s inbox. They receive your message and can choose what to do with the information you’ve provided.

When you take notes, you are writing to send a message through time. Instead of sending information through space to other people, notes send information through time to ourselves.

Taking good notes requires a different communication style than what we typically use when writing messages to others. You don’t know when you might need the information again, so it’s important to provide context in your writing. Instead of quick messages or static stories, effective note systems grow over time as you learn new information.

There are three areas to focus on if you want to become a better note-taker:

Building an effective note-taking habit

Converting raw notes into “evergreen” notes

Storing notes with appropriate context to be easily rediscovered

Building an effective note-taking habit

The act of writing notes is a physical representation of thinking. Very often, taking notes is the same as actually doing the work. If you develop a note-taking habit and reference your notes often they will begin to act as a sort of “digital brain.” Unlike your real brain, which is forgetful and probably hungry, your digital brain remembers things with little to no information loss or bias. Tiago Forte is the best resource I’ve found on how to structure your digital brain effectively.

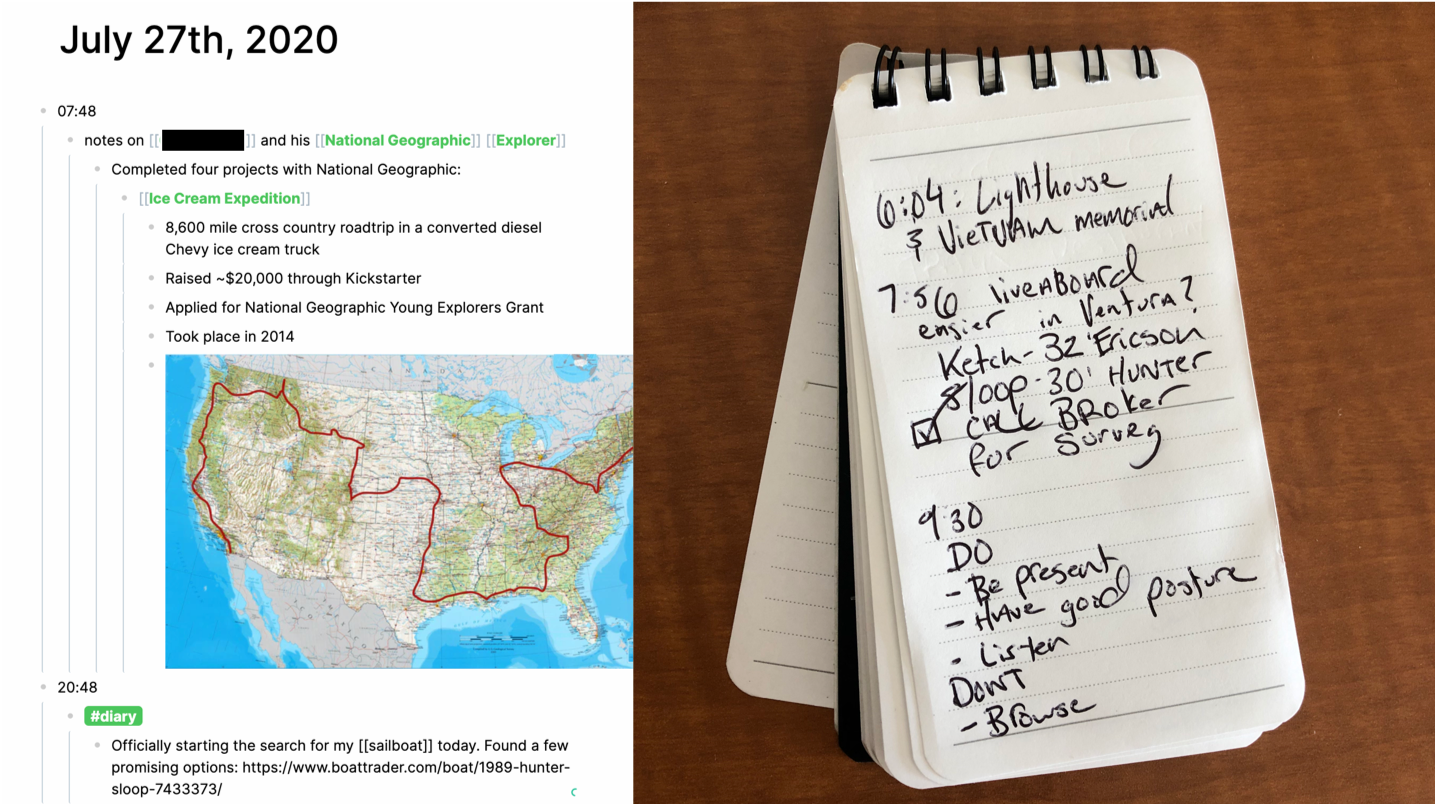

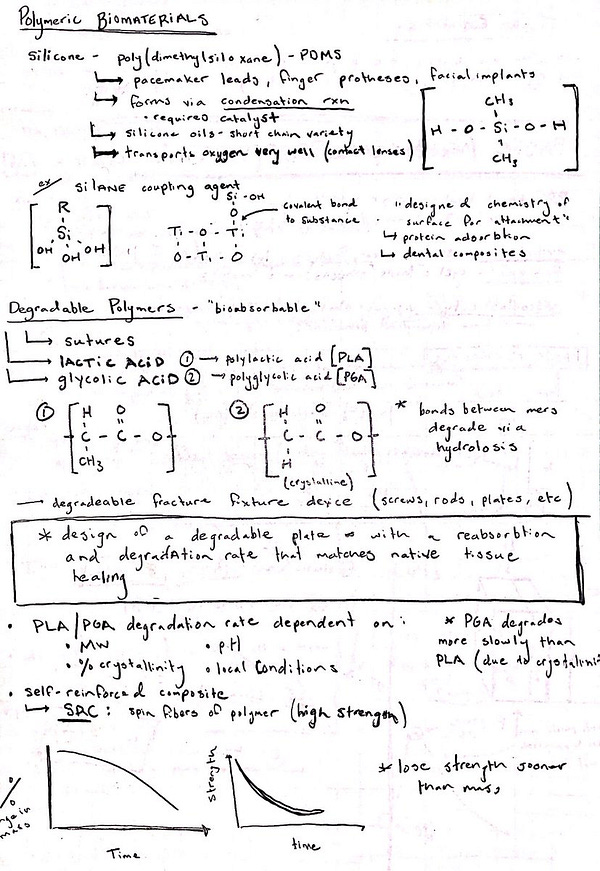

The best way to build a note-taking habit is just to get started. Choose a place where you will consistently take notes and stick to it. For example, I use Roam Research when I’m on my laptop and a small Mnemosyne notebook when I’m out and about.

I use a captain’s log because:

Each note has a time.

Each line has a single idea.

Recurring ideas are designated for follow-up.

Using a barebones format allows me to put things into my notes quickly. These places act as the landing pad for all of my raw, unfiltered ideas and observations. I don’t worry too much about structure or making it pretty. The purpose of this phase is to get ideas out of my head and onto the paper. Minimizing friction is key here.

The next step turns those raw notes into something usable.

Converting raw notes into “evergreen” notes

The term “evergreen” notes is a term popularized by Andy Matuschak and expanded on by Maggie Appleton. They are both wonderful and very thoughtful humans who have a knack for expressing things clearly online.

Evergreen notes are notes that you continue to update over time. Unlike your high school notebooks, evergreen notes do not get thrown in the trash at the end of the school year. Instead, they are tended to by their owners and refreshed as new information comes available.

It took me years to realize these kinds of notes were possible. I was always frustrated by how quickly knowledge seemed to rot out of my head after a class.

Evergreen notes turn those temporary captain’s log notes into something more structured. The key to creating successful evergreen notes from raw notes is to establish a consistent time to reflect and refine. This process can be once a day, once a week, or once a month, but it should be often enough that the raw notes are still fresh when you move them into evergreen format. Creating evergreen notes is more like tending a garden than building a house.

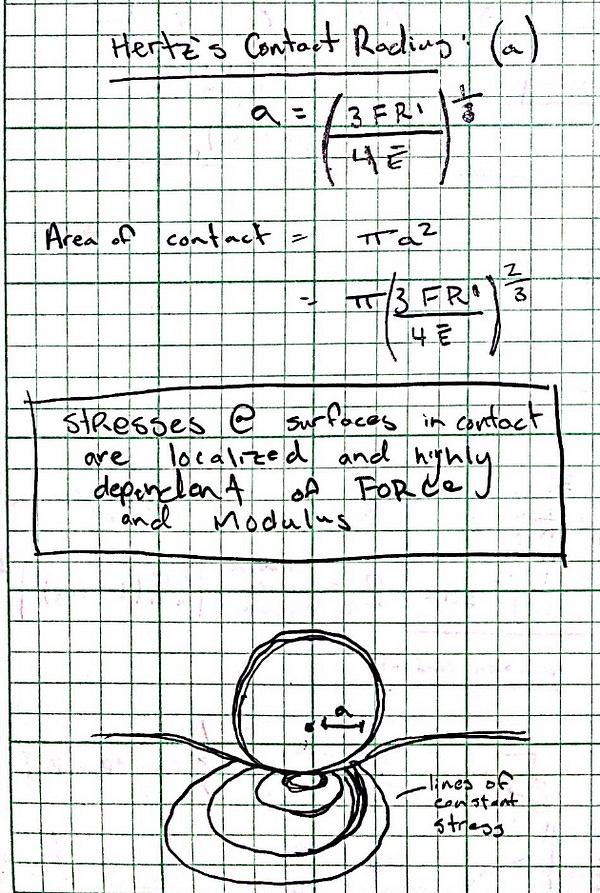

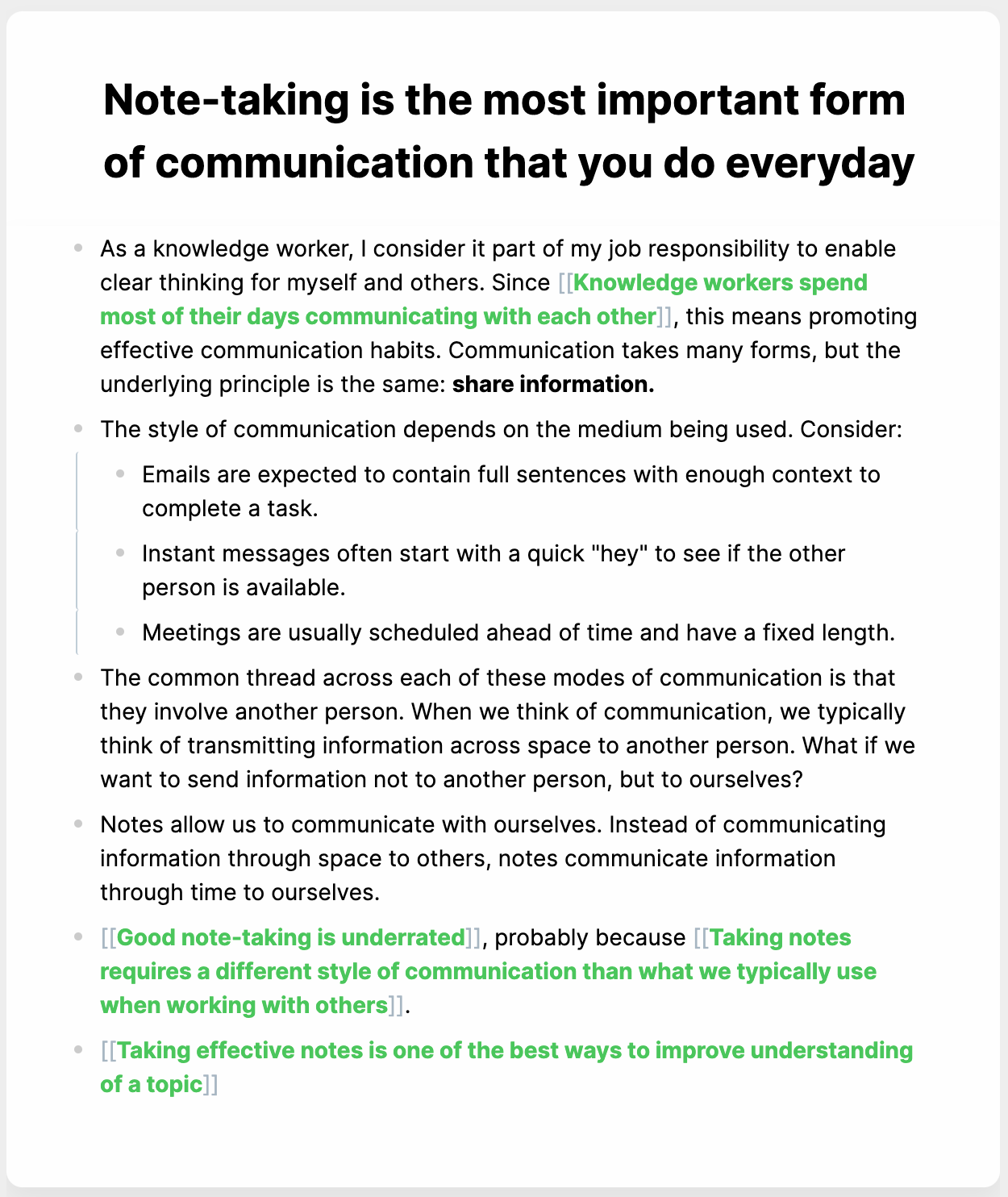

I usually keep my evergreen notes related to a single idea. I express this idea in a sentence and use it as the title of the note. For example, here is the evergreen note that sparked this essay:

Inside of the note are links to related evergreen notes. Related notes are designated with [[double brackets]] and green links. Clicking on any of those links will take you to a short evergreen note where I provide more context and examples of the idea.

I keep related ideas linked by referencing them within each other instead of dumping them into a folder. This system improves my ability to make associations between ideas that would otherwise go unnoticed. I find that this has the side effect of improving creativity.

I define creativity a bit differently than most. Creativity is the ability to put seemingly unrelated things together in a way that creates value. Creating something “new” or “original” doesn’t count — it needs to be valuable too. If you just want to invent something new, try multiplying two ten-digit numbers together. There’s a good chance no one has ever chosen the same sequence as you, but that doesn’t mean your answer is worth anything.

Notes should be structured in a way that maximizes serendipity between ideas. The goal is to “connect the dots” between ideas, not invent entirely new ones from scratch. [1]

The final step in becoming a capable note-taker is making sure that your carefully tended evergreen garden bears fruit. Using your notes to come up with new ideas means being able to find them when you need them.

Storing notes with appropriate context to be easily rediscovered

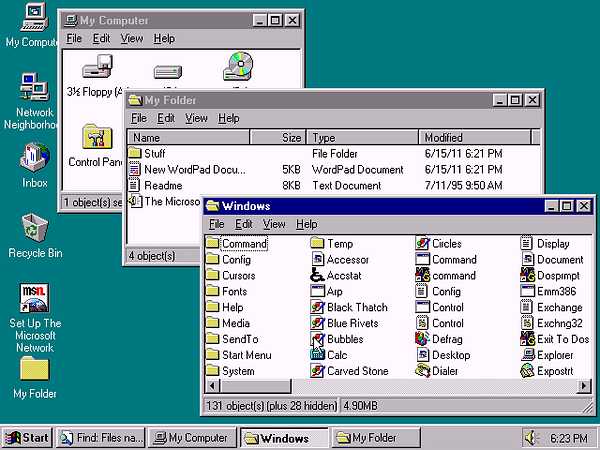

It always bothered me how computers ask us to file away documents in a hierarchy. Folders inside of folders inside of folders. Messy desktops. Whatever the heck a “C:” drive is.

Moving ideas to the digital realm gives us unlimited storage, yet we rely on a system that barely works in the physical world.

The best way to rediscover notes when you need them is to make sure your system is densely linked. Don’t write a note without making sure it references at least one other idea that you’ve written down before. Use your notes as a kind of shorthand: a single sentence might be the tip of the iceberg for a detailed list of observations you have about a topic. The sentence gives you a “hook” to trigger your memory and pull up your digital brain. The more hooks you give yourself, the better chance you have of remembering something when you need it.

It’s not perfect, but you’ll find this system compounding in value over time, rather than overwhelming you. Instead of needing to decide whether an idea goes in Folder A or Folder B, you can just start writing. Over time you’ll make connections between related topics and reinforce associations. New ideas will jump off the page in a way that just isn’t possible when everything is neatly filed away.

Note-taking is my biggest secret to productivity. It seems strange to other people, but I get more returns from my note-taking than any other habit. I recommend giving it a shot if you’re interested in improving your memory or becoming a more effective thinker.

We spend hours every day talking to other people, so why not give some of that time back to yourself? Maybe you’ll realize you’re a better conversationalist than you thought.

Thanks for reading,

Phil

Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that answers simple questions with surprising answers. The author of this publication is currently living from his car and traveling across the United States. You can subscribe by clicking the link below. 👇

[1] If you want to come up with completely original ideas, then taking notes probably isn’t the right approach. For this, you’ll likely want to avoid influences as much as possible - this includes anything you might read or hear. A cabin in the woods is likely a better tool for completely original thought than a notebook.