💠 Sunday Scaries (09/27/20)

Cellular automata, universities are old, practice doesn't make perfect

Hi everyone,

Writing to you from Venice, CA.

It’s surf season in Los Angeles. The waves have been pumping here thanks to a favorable swell direction and offshore breeze. Never one to miss a good session, a few friends and I decided to make the early-morning pilgrimage to Malibu. We were rewarded with ideal conditions: an empty lineup with a wide beach break and great waves. We spent the entire morning in the water, only getting out to grab some food from our favorite local breakfast spot. I’m still smiling ear to ear.

What’s New From Me:

🔒 The Guilty Maker: I wrote this (subscribers-only) post to describe the experience of switching from a manager’s schedule to a maker’s schedule. I’m currently taking some time off between projects to reset and recharge before diving into what’s next. This essay explains why I feel guilty for having free time.

Actions Towards Progress: I’m part of a team putting together a small digital unconference. Our goal is to bring attention to specific actions we can take to accelerate progress in the world. We’re doing this because last year, Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen wrote an article for The Atlantic titled "We Need A New Science of Progress." This sparked a community movement focused on reversing what Peter Thiel calls "The Great Stagnation."

In summary: we've seen lots of progress in the world of bits (information technology, computers), but not much in the world of atoms (medicine, infrastructure, energy).

We use the term "unconference" intentionally. The purpose of these talks should be to spark two-way dialogue. Our event is asynchronous by default, meaning that there is not a designated speaking time -- speakers can upload their videos how they choose and answer questions directly without the need for a centralized organizer. We're simply coordinating the rough outline and theme to build a critical mass of ideas.

You can register here to receive updates about the event.

In This Week’s Edition:

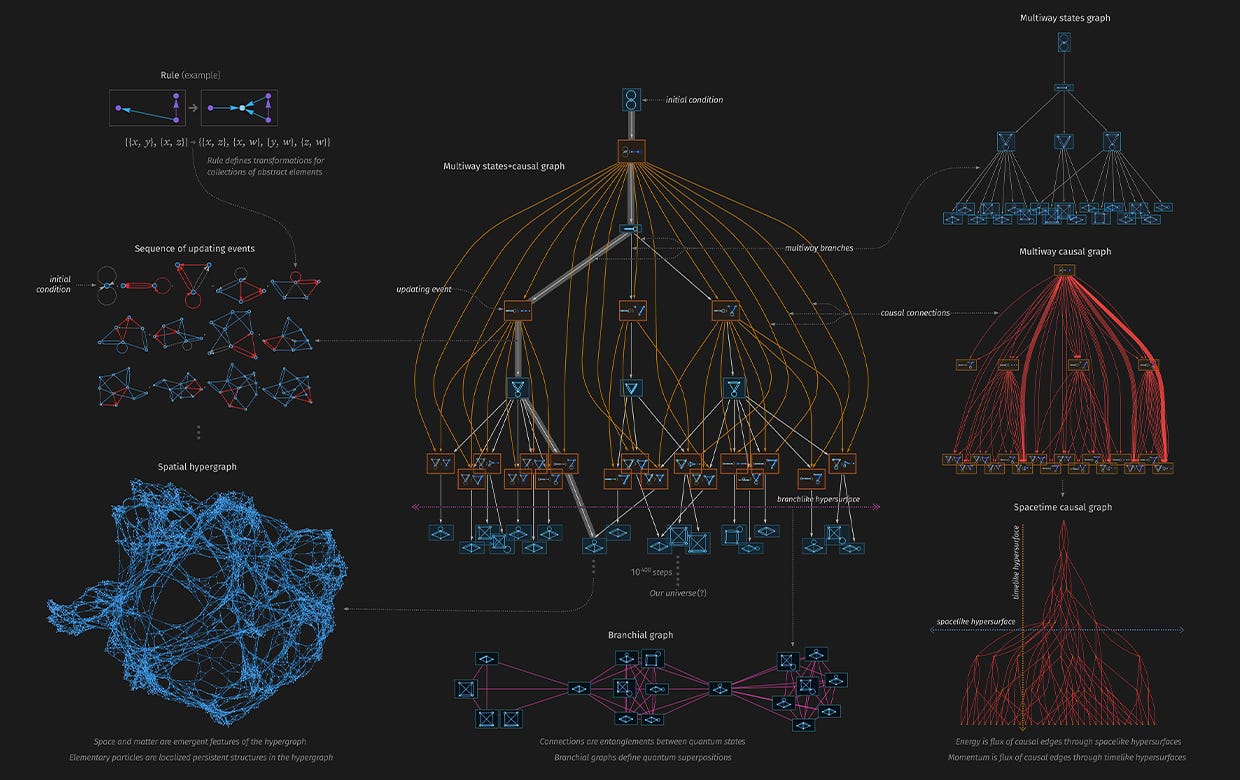

[🔬 Science] New Kind of Science (2002): Cellular automata may provide clues to the structure of our universe. This link will be a rabbit hole of epic proportions for anyone unfamiliar with Stephen Wolfram and cellular automata theory. Simply put, cellular automata states that complex systems can emerge from very simple rules. For a great example of how this works, I highly recommend checking out John Conway’s Game of Life.

This is not the science you were taught in school. A New Kind of Science is a must-read for anyone interested in heterodox ideas, especially because there may be a fundamental theory of physics that builds on the concept of cellular automata. I recommend starting with Rule 30. Proceed with caution - this book is a point of contention in the scientific community.

Lindy score: 2038

[🍎 Education] The strengths of the academic enterprise (1994): Universities are one of the best examples of the Lindy Effect in action. From the essay:

In the Western world, 66 institutions have enjoyed a continuously visible identity since 1530. Among those 66 are the Roman Catholic Church, the Lutheran Church and the Parliaments of Iceland and the Isle of Man. What makes these 66 so interesting —and I owe the knowledge of this fact to our President Dr. Berdahl— is that the remaining 62 are all universities!

This talk is a diatribe against the idea that universities and industry should partner. The author explains why such partnerships inevitably fail: academic institutions have a different Buxton Index than corporations. As described by the author:

The Buxton Index of an entity, i.e. person or organization, is defined as the length of the period, measured in years, over which the entity makes its plans.

The reason universities tend to be so long-lived is that they have very high Buxton Indexes. Corporations, on the other hand, often have comparatively shorter time horizons for planning. Friction builds when each party interprets these differences as intentional offenses:

The Buxton Index is an important concept because close co-operation between entities with very different Buxton Indices invariably fails and leads to moral complaints about the partner. The party with the smaller Buxton Index is accused of being superficial and short-sighted, while the party with the larger Buxton Index is accused of neglect of duty, of backing out of its responsibility, of freewheeling, etc.. In addition, each party accuses the other one of being stupid.

Lindy score: 2046

[🧠 Psychology] The psychology of learning (1921): Most people don’t reach their potential because they lack structured practice. This highly cited work from psychologist Edward Thorndike provides an in-depth review of the existing literature around various learning modes. It’s long, but chapter seven, titled The Amount, Rate and Limit of Improvement, is worth reading.

My takeaway: we should apply the mindset of professional athletes to other domains.

Here’s why: Professional athletes tend to represent the limit of human ability within a narrow domain. Athletes constantly train to hone these skills, often drilling the same maneuvers for years. This isn’t limited to sports: any competitive ventures like playing the piano, speed-running a video game, or winning a spelling bee involve deliberate practice.

Curiously, there is no analogous process for professionals, who often perform the same job for years with little to no measurable improvement. Because there is no way to practice other than doing the work, people tend to stagnate. Imagine if professional athletes never hit the gym or practiced drills, but only played games as a form of practice. This is the reality for most people who never find the time outside of work to improve specific aspects of their performance.

What is the analogous practice routine for, say, a teacher, or an accountant? How about the CEO of a company? We’re stagnating not due to a lack of ability, but because there is no structured form of practice for many professions.

From the book (emphasis my own),

On the other hand, the efficiency possible in any one such function in the case of an ordinary person, who gives enough time and interest to well-advised practice in it, is, I am convinced, often underestimated. The main reason why we write slowly and illegibly, add slowly and with frequent errors, delay our answers to simple questions and our easy decisions between courses of action, make few and uneven stitches, forget people's names and our own engagements, lose our tempers, and the like, is not that we are doing the best that we are capable of in that particular. It is that we have too many other improvements to make, or do not know how to direct our practice, or do not really care enough about improving, or some mixture of these three conditions.

If you’re wondering how to apply this to your own life, consider starting with a deliberate note-taking practice. For further reading on this topic, Andy Matuschak’s notes are the best place to start.

Lindy score: 2119

Thanks for reading,

Phil

Sunday Scaries is a newsletter that focuses on content that has stood the test of time. Because of The Lindy Effect, the topics covered will still be relevant in the future. You can subscribe by clicking the link below. 👇